People sometimes ask me how I started writing, which I don’t know how to answer, since it always felt like a need clawing its way out of me. But now might be a particularly good time for the story of my first book…

Last week I was in Athens, Ohio, which—oddly enough—is where my first book was born in the autumn of 2004, exactly twenty years ago. I had no idea that would happen at the time. I was just a young anarchist in Harrisonburg, Virginia, at a time when most anarchists in North America didn’t know comrades in other cities, unless they were anarcho-punks who travelled in the music scene or people who had been around a while longer in places like the Bay, Seattle, Detroit, NYC, Montréal…

I guess I knew a couple people. Helping out with preparations for the protests against the World Bank, I met a few people from the Brian MacKenzie Infoshop in DC, in the way that maybe they don’t notice you because they’re a lot cooler than you are, or maybe they think you’re a snitch because you want to make friends with them. The protest was pretty tense, since it was December 2001 and pretty much everyone but the anarchists pulled out after September 11th. I went with my best friend from elementary school, but the whole Black Bloc got kettled by riot cops fast, and the only thing I had on me to throw was a banana…

The following July I met Sue Daniels, an anarchist from the generation before me, from Blacksburg, Virginia. She laid much of the groundwork for the growing movement against mountaintop removal coal mining in Appalachia, and later we would get a chance to roll in the streets together in the riots against the Republican National Convention in NYC, the year she was killed by an abusive ex. We met, though, as codefendants, having been arrested with about forty other people on the military base in Fort Benning, Georgia, at a protest against US militarism in November. And during my six month prison sentence, I met another anarchist about Sue’s age from West Virginia, Greg Michael. He taught me yoga and stole me food from the kitchen to help me with some health problems I was having. His twelve year sentence ended up killing him. Fortunately he got about half a year on the outside before the heart attack, caused by a whole decade of stress, confinement, and bad food. The eventual book would be dedicated to both of them, and they each found their way into it with the things they taught me.

It was a moment in history of intense pacification, even as the tonnage of bombs the US was dropping on people in Afghanistan and Iraq was increasing. In the first year or so after the attacks on the World Trade Center, the only folks who were really taking to the streets or trying to stop the gears of mass slaughter were militant anarchists and committed pacifists – Catholic Workers or dissident friars like Jerry Zawada, who I shared a cell with my first week on the inside. In 2003, the mass protest groups enacting Gene Sharp’s CIA-supported style of nonviolence only needed a few weeks to kill off the antiwar movement.

Then in November 2003, I caught a ride with some anarchists from Baltimore to head down to Miami for the protests against the Free Trade Area of the Americas (“NAFTA on Steroids”). We were listening to Against Me! the whole way down, and I got to drive the van through the night. One of the friends on the van died of meningitis right after the protest, while everyone was still reeling from the police repression. The cops had attacked the Black Bloc with tear gas and rubber bullets, and once we were dispersed they followed us with helicopters and sent plainclothes snatch squads roaring down on any small groups they found. They would squeal around the corner in an unmarked car, thugs would get out, beat everyone down to the ground, throw one or two people in the back of the car and drive off, leaving their friends trembling on the pavement. They put the people they kidnapped in cages, and they sprayed people with cold water or pepper spray, they tortured people, they raped a couple comrades. Hundreds of them participated in this, many others watched and laughed, and not a single one of them testified against their colleagues, from the riot units to the desk clerks. Truly, all cops are bastards, and anyone who tries to defend them with talk about bad apples or reform is a bastard as well.

Most of us escaped, though, with a lot of Black neighbors helping people change their outfits or inviting fugitives into their homes.

I took off over a fence and through a park with a comrade I recognized from the van. We climbed way up a tree to hide from the helicopters and snatch squads. She had a think Baltimore accent. We ended up smooching until night fell and we crept down to go our separate ways, but we kept in touch. She kept organizing and became a teacher back in her city.

There was a bit of a lull in Harrisonburg. Our first infoshop had been evicted. Food Not Bombs was still going, this was before the vegan university students in the group got mad that the houseless folks who had started helping cook and set up—people the students never spoke with—were donating ingredients that weren’t up to their dietary codes. Our Anarchist Black Cross chapter was in a nascent form, just writing to some long term prisoners, and we hadn’t started Cop Watch or the next social center yet.

So when I heard about the grandiose-sounding 2004 North American Anarchist Convergence, I was pumped. I even signed up to speak on a panel – they were specifically looking for someone to speak in favor of the “Violence” position on a “Nonviolence vs. Violence” panel, and no one else was dumb enough to be the straw man I guess. I spent weeks before the convergence doing research, planning out what I would say.

When the time came, Patrick—my best friend in Harrisonburg—and I got into his car and drove west and north on route 33, clear across Appalachia to the foothill town of Athens. I was driving a taxi to pay rent at the time, so it was easy to take off for a half week (we weren’t technically employees: we paid $50 to rent the taxi for 12 hours and had to return it clean and with a full tank. Anything over 50, we kept. There were some days when I drove 12 hours and ended up owing money, but on the whole it worked out, and nearly all in cash).

The Convergence, hosted at a university building an anarchist enrolled at OU had been able to reserve, was intimidating and inspiring. The keynote speaker was Howard Ehrlich, an older comrade associated with the Social Anarchism journal.

(They were really kind to me when I reached out to them with some early writing… but then they ghosted me after they cancelled the publication of a review I wrote for a Chris Ealham book, Anarchism and the City. My review was overwhelmingly positive, since it’s a good book, but I also had a strong criticism where Ealham fudged the actual history and projected a very modern and very silly debate—mass organization vs. insurrection—onto the Iberian anarchist movement of the ‘20 and ‘30s. In the actual history, those two strategies worked hand in hand. Anyway, Ealham and some of his grad students threw a hissyfit, pressured the editors who I guess were also academics, maligned me online for good measure, and that was the end of my relationship with Social Anarchism.)

I particularly remember Ehrlich speaking about alternative institutions, and one of the leaders of the Invisible Committee who happened to be there interrupted him in an endearingly thick French accent to say, “But we don’t want to make banks, we want to burn them!”, probably winning a few enamored followers.

Some CrimethInc. folks were also there, though we didn’t meet. In fact, we barely met anyone, given certain high school vibes the anarchists in those days were notorious for. It’s also possible Patrick and I were just a bit awkward. The night after the main event, we found ourselves at a local bar drinking with A., a new friend from Baltimore who we’d discovered was the publisher of an insurrectionary text Patrick and I both loved. In person he turned out to be a real sweetheart!

It’s not my story to tell, but A. remained a dedicated anarchist. He ended up moving across the country and almost dying in one of the uprisings of the following decade. Nearly ten years after we met, I found myself in his living room after a book talk. It was such a gift to be able to look back in time in a sudden flash and see how much things had changed!

Anyway, my panel ended up being pretty dumb. No serious critic of nonviolence is going to describe themselves as a champion of violence unless it’s for shock value, because the dichotomy itself is one of the central weaknesses of nonviolence. So I knew the panel I’d volunteered for had been designed by people who didn’t understand or didn’t respect the framework of a diversity of tactics. What I didn’t know was that the two other panelists were a painfully liberal old-school pacifist and a slick grad student who was an advocate of one of the newer rhetorical models of nonviolence. He was also the moderator. We ended up butting heads again the next year as he and another academic tried to impose their middle class truth on the movement against coal mining.

The whole panel was designed to silence any real criticism of nonviolence. First the one guy went, then the other, both of them using ready-made clichés and false histories that mainstream society already instructs people in. The only way to rebut these arguments is to delve into suppressed histories or deconstruct arguments that appear to be commonsense, but the moderator only allowed me 5 minute segments to respond to each ten minute chunk of pacifist bullshit. Two or three rounds, and then questions. The whole thing was over in under an hour.

It was so frustrating, I had done so much research to prepare, and I barely got to use any of it! The other two panelists weren’t interested in solidarity or sincere strategic debate at all! They just wanted an easy chance to dunk on some dupe, reinflate their feeble dogma, and pad their egos.

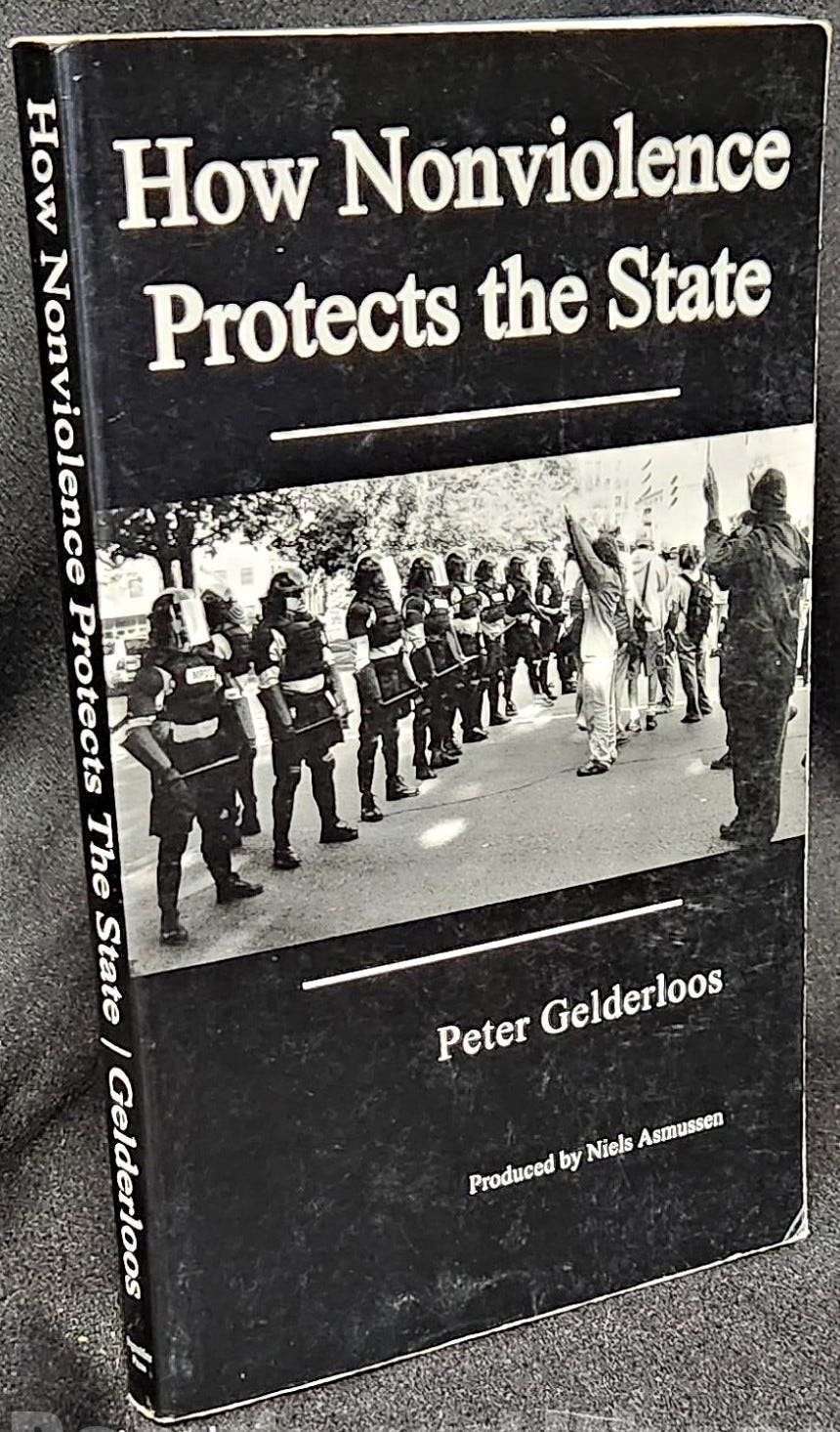

I resolved to write up my arguments as some sort of essay or zine. I had grouped my research and arguments into six different themes. That became the outline. But the more I wrote, the more I wanted to develop the arguments and flesh out the silenced histories. The paragraphs multiplied, the pages grew, each theme became a chapter, and after a month of writing what I had was far too long for a zine.

I had written a book by accident. Which was funny, because at least thrice I had tried writing a book on purpose and failed each time: a fantasy novel that was stuck halfway between Tolkien and bad allegory; a grim, absurdist, philosophical novel comprised of existential dialogue amongst a boatload of Vikings as they sailed back and forth between home and pillage in the British Isles (and there was definitely one sad, starry-eyed marauder who was a literarily clumsy stand-in for myself); and then “As Long As There Are Bars,” the nonfiction work I wrote a hundred pages of trying to show that prison and policing are omnipresent in our society. To wit: “there’s no such thing as in front of bars: as long as there are bars, we are behind them.” Anyway…

So what to do with a book manuscript? Well, anarchists self-publish all the time, don’t they? And I had started saving up money from the taxi job for what I thought would be a yearlong trip hitch-hiking and staying in squats around Europe, learning languages and absorbing lessons from the anarchist movements there. I wasn’t planning on leaving for another year, surely I could pay to print a thousand copies, sell them all and make my money back in a year, right?

Fortunately I knew absolutely nothing about the book business.

And, I had a friend who had a pirated copy of InDesign and knew how to use it: he did the layout and the design, and we published it under our own imprint: Signalfire Press!

I called up all the radical bookstores in the country I could find out about—close to a hundred—and got most of them to stock the book. That was a whole lot of trips to the post office! I started going to anarchist bookfairs – Montréal and Baltimore. In Baltimore I got the book into the hands of an editor at South End Press, one of the more respected leftist publishers at the time. They would end up publishing the second edition of the book two years later, and then going out of business after selling about five thousand copies. That ended up being the omen I needed to resolve my ongoing internal debate: do I try to make money from writing or not? It would be a resounding no for 18 years. All the money would go into printing costs, travel costs if I was doing book talks, and supporting movement projects.

It was a sensible decision for someone who was young, squatting, writing things no larger publisher would touch, and able to grit their teeth through the chronic health problems that came up along the way. Maybe not so sensible for someone paying rent, older, no retirement plan or savings, short on grit, and with some additional health problems.

But in that moment all those considerations were in an unknown future. I had just sent a fiery polemic out into the world, managed to distribute all the copies in a year, and would soon be immersed in the ongoing strategic debates unfolding across multiple continents.

That’s the story, less of an end, and more of a beginning.

https://detritusbooks.com/products/how-nonviolence-protects-the-state-by-peter-gelderloos

And for free on The Anarchist Library

To Sue and Greg, with love.

Just a correction from my muddled brain: Left Bank Books in Seattle never published "How Nonviolence Protects the State"...

but they did publish my 2013 follow-up, "The Failure of Nonviolence," in which I try to orient more towards the dominant Gene Sharp/NGO variety of nonviolence, the State Department backed "Color Revolutions," and all the meaningful revolts taking over streets and entire cities in the years between 2005 and 2013.

This was really fun and an interesting/inspiring look into the behind the scenes stories to your first book. Thank you for sharing! I was in high school during a lot of the stuff described, but I still love hearing all the stories from the period right before I was able to be involved. Living in rural Canada it all seemed so far away, save for the message boards I was able to be a part of.