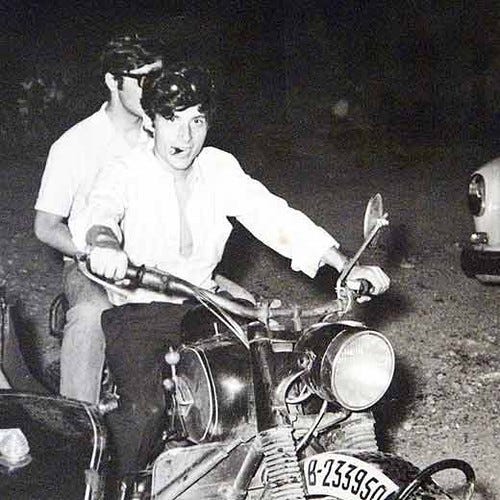

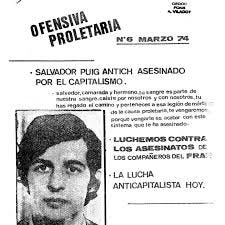

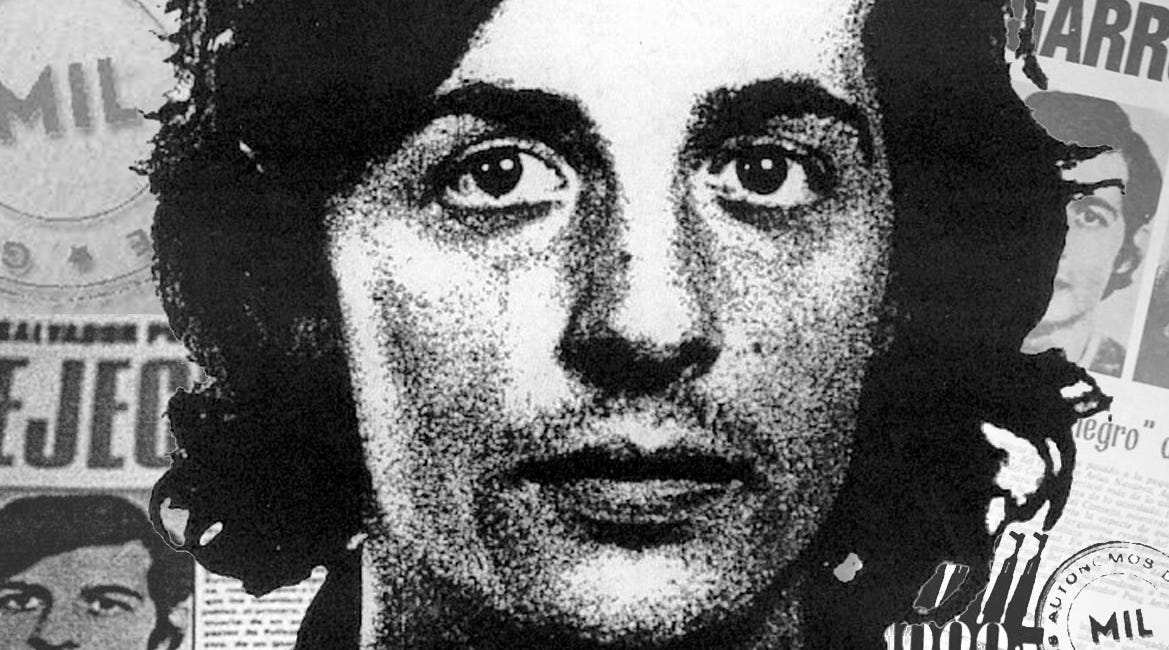

Today, 51 years ago, Salvador Puig Antich was executed by garrote in the Modelo prison, Barcelona. Salvador was a young anarchist and part of the MIL, Movimiento Ibérico de Liberación, an anticapitalist armed group that included other anarchists alongside anti-state Marxists, active in Catalunya in the last years of the Franco dictatorship. The group was part of a broader workers’ movement, robbing banks so they could give money to strike funds and support the families of people imprisoned or killed in the struggle. Old anarchist exiles living across the French border in Toulouse gave them their first weapons and taught them how to shoot, how to sabotage infrastructure, and how to rob cars.

This same network of old revolutionary anarchists who had survived the clandestine struggle of the ‘20s,’30s, ‘40s, and ‘50s, as well as the revolutionary conditions of the Spanish Civil War and the struggle for survival against the Nazis in World War II passed on these skills at a global level. They gave the first weapons and forged documents to groups like ETA in the Basque Country, the Tupamaros in Uruguay, and the Angry Brigade in the UK. Probably the first manual on urban guerrilla warfare was written by the Spanish anarchist Abraham Guillén, who escaped prison and fled the Franco regime in 1945, subsequently living clandestinely and participating in revolutionary struggles in Argentina, Uruguay, and Peru. In 1966, Guillén wrote Strategy of the Urban Guerrilla, and over the following decades he authored several other volumes on the theory and practice of revolutionary struggle. Pushing back on some points in the doctrine of the rural guerrilla developed in the Cuban Revolution, Guillén wrote the introduction to the Uruguayan edition of Che Guevara’s Guerrilla Warfare. As a whole, the decades of experience cultivated by the Iberian anarchist movement, experience with both clandestine and open struggle, in urban and rural environments and connected to revolutionary examples of self-organization, was a major influence on revolutionary struggles throughout the 20th century in France, Italy, Germany, the UK, Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, and beyond. Authoritarian tendencies on the Left have been highly successful at erasing this part of our history.

In one of their earlier actions, the MIL stole a printing press, and throughout their existence they distributed thousands of copies of clandestine publications, texts by the anarchist Camillo Berneri, the Situationists, or council communists, and a whole revolutionary library made available to the workers’ movement through a network of safe houses, also maintained by bank expropriations. They started a magazine, the satirically named International Anarchist Conspiracy, “CIA” in Spanish, and the publishing group, May ‘37 Editions, a reference to the anarchist revolution in Spain and the 1937 counterrevolution, led by the bureaucratizing leadership of the anarcho-syndicalist CNT working together with the Communist Party, the Socialist Party, and Catalan independence parties.

Notably, the workers’ movement of the ‘60s and ‘70s that helped bring down the Franco dictatorship, the longest lasting fascist dictatorship in the world, was mostly a wildcat movement that used direct workers’ assemblies to self-organize. The Communist Party and other factions did their best to bureaucratize, pacify, and control it for their own interests, a tendency that the MIL and many other groups were fighting against. In the end, the workers created a destabilizing crisis, but not a revolution: the Communists and Socialists gained enough power over the movement that they could kill it through compromise just like they did in 1937. They shook hands with the fascists, who rebranded as conservatives, and together they transitioned the whole lethal machine to a democracy, which still exists today, getting away with the same forms of repression and exploitation, but with even higher profit margins.

Salvador was arrested in a shootout with police in the fall of 1973. He and a cop both got shot. The cop died. Most of the rest of the group was arrested, everyone was tortured. One, Oriol Solé Sugranyes, was shot down by the guardia civil after a prison break.

I learned plenty of these stories when I began helping some older friends organize yearly events to commemorate Salvador and other fallen revolutionaries. The key lesson was that history cannot be entrusted to the institutions. We have to fight to keep it alive and to pass it on. When we can, we have to give these stories roots in the places where they occurred, carve reminders into capitalism’s amnesiac façade. When we must, we have to learn how to carry our stories with us, through the exiles and diasporas caused by warfare, genocide, repression, gentrification, impoverishment.

I talk about Salvador because he was a close friend and comrade of Ricard, one of my older friends. And those relationships matter, the stories of specific people matter. But it’s important to go beyond that, so the history of an entire struggle isn’t limited to singular heroic symbols, typically younger men who die in the struggle. Likewise, histories of an entire society in rebellion must not be reduced to the hagiographies of single organizations. The organizations singled out retroactively to play this role are often ready for the part: it’s no coincidence that they are disproportionately vanguardist groups with an acronym and a logo, often populated by the children of the elite, like the Weather Underground, the Red Brigades, the RAF.

It’s telling that, while many people across Spain and even in the US might know about the MIL, very few people know about the OLLA—which carried out many more armed actions—and that the OLLA itself is, one some levels, a fiction invented by the Francoist police. The actions were real, the revolutionary women and men carrying them out were real, but the acronym OLLA was created by the police and the press. In reality it was a network of clandestine, armed groups that intentionally never gave themselves a name or an identity to avoid some of the vanguardist pitfalls of other armed groups. For them, the armed actions were just another necessary part of the struggle, same as the wildcat strikes, the prisoner support, the debating, writing, and distribution of subversive ideas…

Collectively, this movement was opposed to the authoritarian, pacifying presence of political parties and critical of the labor unions, with their tendencies towards bureaucracy and hierarchy. Instead, they favored a multiplicity of spaces of self-organization – workers’ assemblies and neighborhood assemblies and more. And they learned from the systematic betrayals by the authoritarian Left – common fronts and coalitions in which the Party could use the base as cannon fodder and keep the radicals under their thumb, ready to sell out the moment a favorable compromise with Power became possible. Owing to this history, many of them deliberately didn’t call themselves antifascists: they were against capitalism whether it wore the mask of dictatorship or of democracy. And learning from the sectarianism and vanguardist ego of the armed groups, they weren’t proponents of “armed struggle.” Instead, they developed a uniquely anarchist current they referred to as “armed agitation,” seeing the struggle as belonging to everybody, consisting of all non-authoritarian methods, with armed actions and sabotage being just another part of the toolbox.

You can learn all about this and more in the book Ricard authored and edited about Salvador Puig Antich and the broader movement (it has texts by Ricard, by Salvador, and by other participants in the movement). I translated it into English and published it with AK Press a few years back.

And you can check out this newsletter I wrote last year, the 50th year anniversary of the execution, thinking about the loss of friends and comrades more broadly.

We Carry Them With Us

I sat down to prepare the talk I have to give this afternoon about a friend who died in the struggle. But my mind is flighty, my breath shallow, shadows of sadness and anxiety, so first I’m writing to you.

Incidentally, I spent a few days in la Modelo, where Salvador was executed, back in 2007. I had been wearing my contacts when I was arrested so I was completely myopic by the time I got to the prison. I only got to know the smells, the colors, the sounds of it. Now, following the American model, it’s been decommissioned, replaced with huge rural prisons that are hidden from view and much harder for loved ones to get to. And following the progressive model, it’s been partially turned into a museum about the horrors of the dictatorship (as though people aren’t also tortured in the prisons of democracy).

Instead of erasing him, like they do to so many others, those in power haven’t tried disappearing Salvador. Their strategy is to turn him—and by extension, turn an entire movement—into a struggle against fascism and implicitly, in favor of democracy. Some try to turn him into heroes of Catalan liberation. And although the cultural and linguistic occupation of Catalunya by the states of Spain and France was an issue with some importance for people like Salvador and Oriol, they were never fighting for the creation of a new nation-state.

So many of these lessons are still relevant. In the last decades we’ve risen up again and again. We’ve had more opportunity to see that elections don’t make us free, no matter how progressive the candidates, no matter how far-reaching the referendums. And when a struggle against one form of oppression becomes de-linked from fighting all forms of oppression, when we trust in methods and solutions our own history could tell us will never lead to liberation, our struggles become self-defeating or we exhaust ourselves, butting our heads against a wall we refuse to see.

History is a weapon. In the hands of the State (or any who wish to reform the State), it’s a weapon against us. In our hands, it can show us paths to liberation.