Eight years ago today, on 15 March 2017, we learned of the death Joaquina Dorado, a lifelong anarchist and fighter. She had passed the day before, after an accident at home. She was two months and ten days shy of 100 years old.

Born in a fishermen’s neighborhood in A Coruña, Galicia, on 25 June 1917, she emigrated with her family to Barcelona in 1934 and went to work in the furniture industry, where she learned the trade of upholstery and varnishing. Living in the Poble Sec neighborhood, she quickly joined the woodworkers’ union of the anarchist workers’ confederation, the CNT.

In July 1936, the left-wing government largely folded in the face of a fascist military coup, but organized workers’, primarily anarchists, defeated the fascists in Catalunya, València, Murcia, Asturias, Cantabria, Euskadi, and large parts of Castilla, Aragón, Extremadura, and Andalucía (basically, half of Spain). A revolutionary situation had broken out. With the fascists and military defeated in many places, the prior government effectively imploded, and no political party in charge of the situation, armed workers and peasants could determine their own destiny. They largely abolished the State by organizing through direct neighborhood and workplace assemblies or through the CNT. However, they made a fatal mistake by giving renewed life to the political parties by working with them in united front, antifascist committees, and by not abolishing the government in Madrid. Likewise, the CNT should have lent its structure and resources to prioritize these new forms of self-organization (both the Defense Committees and the various organs for the self-organization of the economy), but by participating in the antifascist government, the labor confederation became increasingly bureaucratic and hierarchical.

It was a difficult situation, though, with much to accomplish. Dorado quickly became secretary to the head of the woodworkers’ union in Catalunya, Manuel Hernández, and then when he left for the front, she was voted by the other workers into the top post.

In May of 1937, the inevitable counterrevolution arrived in Barcelona, led by the Communist Party, with significant participation by the Socialists and various bourgeois Catalan parties. The month prior, the Communists had gotten more bold in executing anarchists and suppressing worker and peasant assemblies in the Aragonese and Catalan countryside. When they saw that the CNT leaderships, their collaborators in the antifascist government, didn’t protest, they increased the scale of the repression, assassinating many of the more radical anarchists in Barcelona.

Joaquina managed to survive the repression, and the rest of the civil war. In 1939, with Franco’s victory, she escaped across the border to France just as World War II was breaking out. She was put in three different concentration camps, escaping each time, and she participated in the clandestine resistance throughout the war. For a time, she secretly lived in Montpellier in the house of the botanist Paul Reclús, nephew of Élisée Reclús.

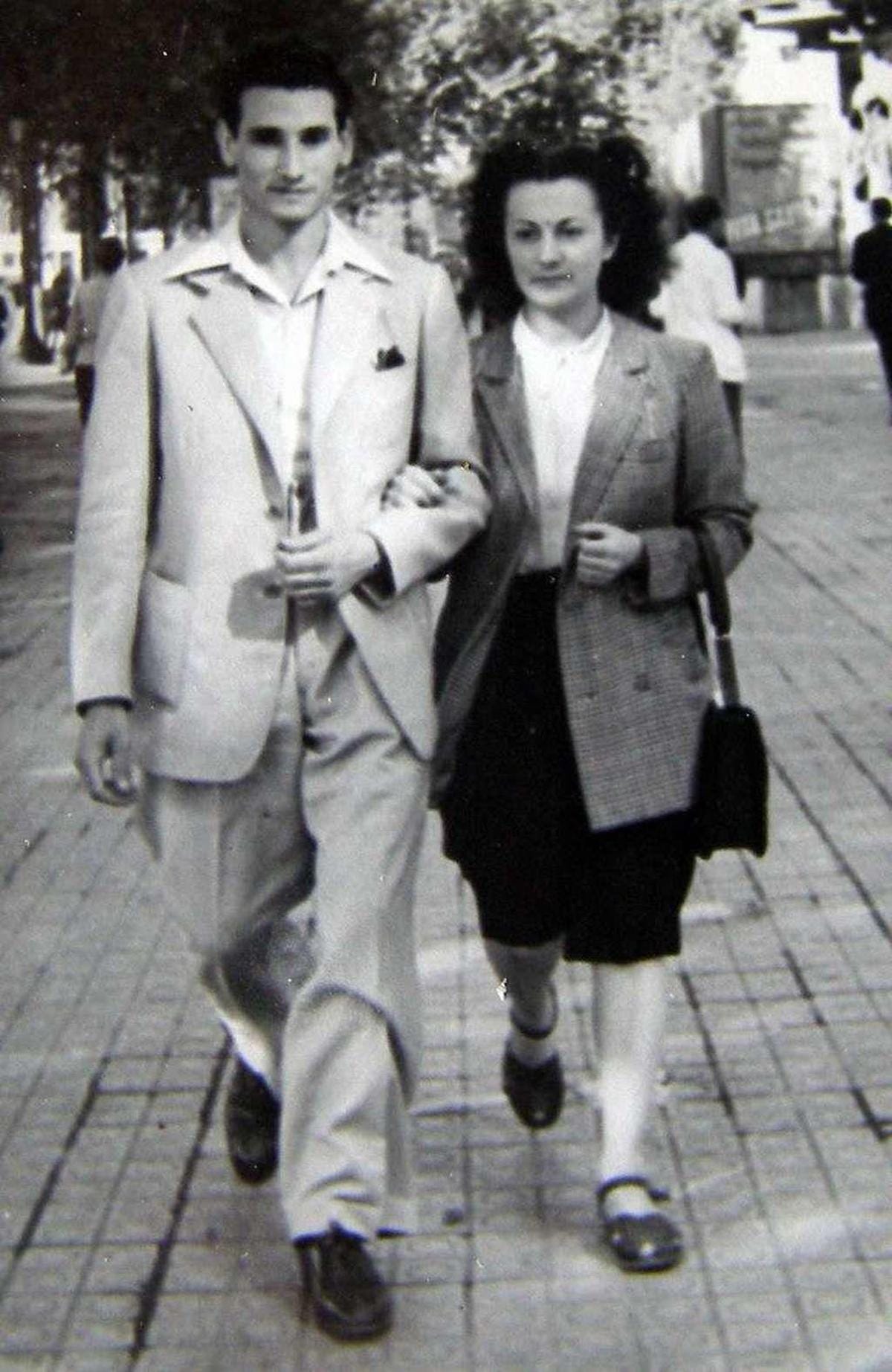

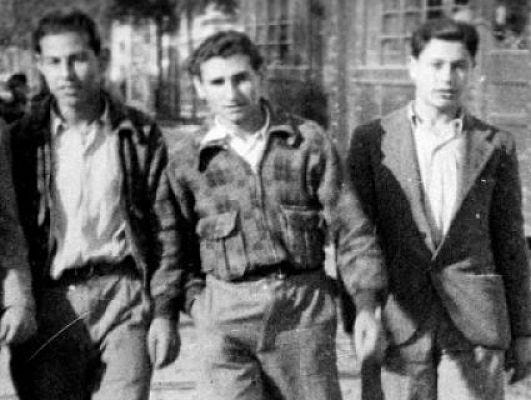

From exile in France, she helped reconstitute the woodworkers’ union and to strengthen the FIJL, the anarchist youth federation, which was one of the bulwarks of the struggle throughout the civil war and in the first decade of clandestine resistance. With her lifelong companion, Liberto Sarrau, whom she had met in Barcelona in 1936, she helped form the 3rd of May group, a revolutionary affinity group that participated in the armed struggle and published a clandestine anarchist paper, Ruta (Path). Other members of the group were Raúl Carballeira Lacunza (1918-1948), Francisco Martínez Márquez (El Clot, 1922, shot down on the street of Rosselló, Barcelona, 21 October 1949), and Germinal Gracia Ibars (1919-1991). In 1946, she snuck back across the border into Spain to continue the guerrilla resistance there alongside other anarchists like Ramón Vila Capdevila (Passos llargs) and Quico Sabaté. They carried out actions of sabotage and expropriation to support the continuing workers’ struggle under fascism. Her name in clandestinity was la Nuri.

She and Sarrau were captured in February 1948, tortured for 18 days, and then held in prison for the next several years, given conditional release then imprisoned again for continuing her anarchist activities.

In the photo above, taken in 1948 from the prison yard at Les Corts, we see (left to right, starting with those standing) Margarita de la Torrassa, Manuela Sáez, Francisca Avellanet, Joaquina Dorado, an unknown prisoner, and Rosa Mateu. Seated: Dolça de Terrassa, Antònia Martínez de Terrassa, Antònia Martínez Juliana, and two unidentified socialist comrades.

In prison she fell gravely ill, but clandestine networks organized by the CNT secretly got her money to pay for the antibiotics that saved her.

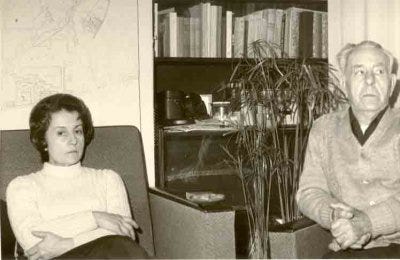

In 1956, after a conditional release, Sabaté helped her get back into France. There she was reunited with Liberto Sarrau, who had managed to leave after 10 years in prison. They were both given political asylum and moved to Paris to continue their anarchist organizing.

They were also close with other anarchists a little younger than them who had grown up in the working class Barcelona neighborhood of Clot (where I lived for 8 years, and also where I met an older friend I’ve mentioned, Ricard, another anarchist fighter and historian): people like the anarchist historian Diego Camacho (Abel Paz), Joan Llarch, and Federico Arcos. The latter went into exile in Ontario, Canada, and developed close relationships with a group of radicals in Detroit who came of age in the struggles of the ‘60s and would form the radical publishing project, Black and Red (publishers of Against His-story, Against Leviathan! and other key texts that I wish today’s radicals would re-read).

After the end of the Franco dictatorship, Joaquina continued her struggle. As many anarchists of the time said, their struggle was against capitalism, in whatever guise it took. Around when Liberto died in 2001, she donated her papers and documents to the social movement archives in Amsterdam and moved back to Barcelona. In the last decade of her life, she continued writing and giving talks at anarchist events about the revolutionary experiences of her generation.

We’ll remember her.

Below are some links for anyone who can read Spanish or Catalan. First a memoriam in English written by David Watson, from Detroit, for Federico Arcos.

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/david-watson-remembering-federico-arcos

https://rojoynegro.info/articulo/in-memoriam-joaquina-dorado-pita/

https://www.diagonalperiodico.net/blogs/imanol/joaquina-dorado-pita.html

https://sobrelaanarquiayotrostemasii.wordpress.com/2018/06/08/federico-arcos-martinez-vida-y-obra/

Thanks for writing this. A nice break from reading about what is going on in the world today.

This was great Peter, I appreciate you writing about some of the lesser known radicals from history. I was wondering what other texts you'd reccommend from Red and Black other than "Against his-story, against leviathan!"? I'd be interested in checking some out.