A decentralized, ecological revolution is not only necessary, it’s our best chance for survival. To understand what that even means, we need to explore the concept of rooted networks. Once we understand how such networks are uniquely potent, intelligent, and resilient, it becomes clear that the entire mainstream spectrum—even what is considered radical in the mainstream, but still gets featured in the New York Times—actually shares many fundamental features in common. From authoritarian socialists ensconced in universities to democratic environmentalists like the Extinction Rebellion leadership to the reformist scientists who participate in the IPCC to green capitalists like Bill Gates to tech fascists like Elon Musk: all of them trust in the State as an instrument of change; all of them believe the world can be effectively molded and improved by experts and leaders imposing blueprints; all of them advocate maintaining many of the institutions that arose as a part of global colonialism and are instrumental in maintaining it.

On February 3, I published an article with In These Times, “Betrayed by Green Capitalism, Here’s How We Can Build a Livable Future.” To stick to the word count and not end up with a 30 page article, I decided to publish a lot of sources, explanations of research, and additional details in several parallel newsletters. Honestly, I think there’s enough here for a book.

Here’s the link to Part I, which gives the data for the assertion that the mainstream climate framework—which consists of emissions reductions targets, carbon accounting, industrial-scale green energy investment, and “green growth” or supposedly sustainable capitalism—has no chance of working.

“The Facts that Back an Ecological Revolution: Part I”

The Facts that Back an Ecological Revolution

Today’s newsletter is a companion piece to my new article with In These Times, “Betrayed by Green Capitalism, Here’s How We Can Build a Livable Future.” It’s here for anyone who wants to dig into the data, check my sources, learn more, or understand how fraudulent the official climate framework really is (that’s the framework centered around the Paris A…

Finally, it’s time for Part II, a deeper look at:

Rooted Networks

“ Rooted networks are ecosystemic and interdependent. They allow for everyone to define their own needs, to build their own relationships with their specific habitat, and to share resources and feedback throughout their habitat and across the entire system.

The basic operating principles of rooted networks are:

Build a habitat that ensures health and survival for you and those around you.

Don’t pursue interests that poison the habitat.

Turn difference into strength so that the members of the ecosystem fit together in a complementary way.

Conflict or contradiction don’t mean war: work through it and grow from it, or give it some space and allow different habitats to exist side by side.

Help these communities learn what they can share, to form part of an integrated global ecosystem.

"

What follows are a series of discussions or explanations, with links and documentation, that demonstrate some of the points I summarized in the In These Times article, about the advantages and applications of rooted networks.

Society against the State:

The State exists in opposition to society and ecology, and over time states tend to harm their societies and destroy the environment. In Worshiping Power, in which I research dozens of examples of state formation and state collapse on every continent, from the 20th century to 5,000 years ago, I look at how states rest on the imposition of centralization and hierarchies, which are the opposite of rooted networks, and which require the weakening of such networks, resulting in a great loss of social intelligence through the shedding of complexity in language, diet, ecosystemic awareness, gender, social and familial relations, and connectivity.

I also find a solid pattern supporting the idea that all states are ecocidal and many states throughout history have collapsed by destroying their own soil and ecosystem, or they have been overthrown by their own subjects and neighbors as their extractivist activities subject people to famine and other forms of violence. And while all human societies have the capacity to wreck their environment, stateless societies are much more capable of understanding the feedback from ecocidal activities, changing course, adapting, and shifting away from extraction, whereas states tend to lock themselves into accelerating forms of extraction, which means more intense exploitation and impoverishment of their subjects, and an additional motivation for conquest-oriented warfare to steal more land and more non-consensual subjects (slaves). Where there is a centralized apparatus that controls the direction a society takes, as is the case under the State, those with the power to make the decisions have a vested interest in rejecting dialogue with the Earth, ignoring the consequences of their action, and intensifying their strategies for exploitation and control.

Currently, there are no strong, evidence-backed arguments for the validity and favorability of states. When the argument is made, it is usually on the spurious grounds that domination by states is “natural” or inevitable, or a zero-evidence assertion that decentralized networks only work at a small scale. This argument is also a complete misunderstanding of the concept of scale. A population of a billion can organize at a large scale or at a small scale, and in fact it takes much more energy to organize them at a large scale. There is also a large cost to doing so: forcibly shedding their complexity, pacifying them, and removing most of their agency, input, and power. On the contrary, small scale organization allows everyone to make the fullest use of their own strengths and advantages. In other words, small-scale organization is perfectly applicable and perfectly relevant to a world with 8 billion humans. Organizing those 8 billion humans in a large-scale, centralizing manner, as is the case today, requires constant warfare, policing, surveillance, inefficient and unsustainable economies of forced dependency, alienation, enclosure; and all of these things prevent us from self-actualizing, they prevent us from developing and applying our intelligence, and they prevent us from exercising our agency. Under the State, we can’t fully become people.

Another spurious argument that defenders of the State will make is that decentralization can’t work. They refuse to admit that it has for most of human history. They refuse to admit that the major ingredients that have allowed the State to spread globally have been military conquest, genocide, mass enslavement, artificial scarcity, and forced dependence. Because the State requires a monopolization of decision-making authority and legitimate force, its very existence negates our freedom to decide the best way to organize ourselves. In other words, defenders of the State erase the memory of other ways of being—with erasure being one of the goals of genocide—in order to cover up their complicity and their ethical responsibility to stand up to the kinds of atrocities and oppressions no one should excuse.

In a truer light, we can see that the tables are actually turned. Rooted networks don’t have to prove their superiority to state organization, hierarchy, capitalism, because the State has already proven it is not a viable option. It’s not even realistic to ask which is the better option: the State and capitalism are currently committing suicide on a global scale, bringing many or most of us down with them.

Decentralized networks are more intelligent and resilient than hierarchies:

There is a strong theoretical basis backed by substantial evidence regarding the resilience and agility of networks, and the intelligence and capacity for self-organization of decentralized, complex structures, far exceeding the capacity of centralized, hierarchical structures like the State. Our educational systems and media tend to suppress or obscure this evidence, as we can see in the demonstrably inaccurate, mythological ideas most modern people have about human history. When our society cannot ignore the evidence of the superiority of decentralization—for example when discussing technological advancements that greatly impact our lives—experts and the media will compartmentalize and depoliticize the topic. So breakthroughs in computing or discoveries about neural networks will rarely use language like “decentralized” or “self-organizing,” instead misrepresenting the principles at work to force them to fit into the dominant paradigm of control, centralization, and hierarchy.

The result is that people are trained to be social flat-earthers, in denial, reflexively ignoring the evidence all around them. Here is some of the evidence:

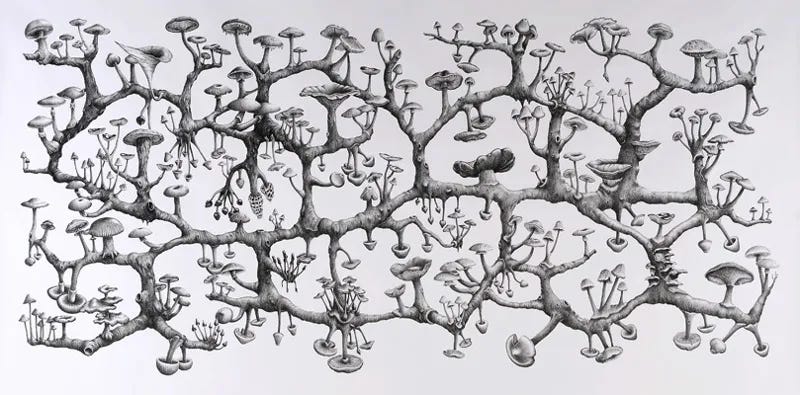

Huge colonies of ants and bees demonstrate effective decentralized decision-making in response to complex problems. Many scientists refer to this as “swarm intelligence”. One feature of their method is high connectivity and information sharing: no single ant has all the information, there is no objective view, no central point where a unified consensus can be formulated and imposed, and that isn’t an impediment, it’s actually a key strength! But every time individual ants come in contact, they share information about how they’re doing and what they’re doing, and every ant combines what they know about their surroundings, their relations, with what they know about their own conditions to make the best decision possible. The greater their connectivity, the more information they share, and the better the decisions they can make, the quicker they can self-organize as a group and complement one another’s efforts, or move together as one if the whole colony needs to relocate, for example. In this way, ant colonies behave like neural networks, which are also decentralized and highly effective. Part of what makes neural networks so effective as the cellular basis of our brains and our sensory systems is their plasticity—their ability to adapt—and their redundancy, both of which are characteristics of decentralized networks. If one nerve gets damaged, there are other pathways for information to travel along, so that whole part of the central nervous system doesn’t have to shut down. If a person needs to start using one part of their brain a lot more, other parts of the network can pivot to increase that specific capacity. The brain’s neural network is certainly decentralized. In what ways is it rooted? So much of brain development is shaped reciprocal interactions between a child and their caregivers (parents, siblings, community), and though brain development slows down after our mid-twenties, our interactions with the world continue to shape our brains for the rest of our lives.

The same methodology that can be found in ants, bees, and brains also manifests in cities and software. In fact, as computer processing technology develops, it goes further and further and further towards principles of decentralization. A key principle is often referred to as emergence, the function of complex systems to be able to organize themselves, in the course of which entirely new properties or behaviors arise. Centralization in a complex system tends to impede emergence, rather than aid it. In other words, centralization decreases the intelligence, the resilience, and the agility of complex systems.

Here’s a good scientific article from 2019 that describes the unprecedented growth and quality of Wikipedia, the largest encyclopedia in the world. In contrast to academia, which is hierarchical, and beholden to state and private funding, and which in many countries like the US is a business, a corporation, Wikipedia functions as a network, self-organizing and self-creating, made by its community of users. The article shows other research consistently demonstrating that Wikipedia is as accurate as standard encyclopedia authored by experts, like Britannica, including in highly specialized topics, and it has an even greater ability to adapt and expand and generate.

Wikipedia is “85 times the size of 120-volume Encyclopedia Britannica”. Many academics reject Wikipedia as a resource due to “jealousy regarding the loss of the knowledge dissemination monopoly” and because of “bias” and an “underestimation of the ability of amateurs to disseminate knowledge in a robust way. As scholars, we should be able to confront and eliminate such biases once we are presented with evidence, and many studies show that Wikipedia delivers high-quality output in practice, even if in theory it may seem impossible.”

The ‘theory,’ mentioned here in passing, is clearly the false assumption that hierarchical institutions are more intelligent.

All of these principles have always been applicable to human social organization. We can see this in the majority of human societies in history that have been stateless, and which have had a far better track record of long-term survival, health, freedom, and ecological sustainability. And we can see it in the pertinence of decentralized computing and digital information systems to modern social organization. It’s also highly relevant in cases of extreme adversity, like the many examples of the self-organized cities that house hundreds of millions of people around the world despite facing high degrees of dispossession and lack of access to resources.

Here’s Raúl Zibechi, writing about urban self-organization as an extension of Indigenous practices and a base for autonomy and rebellion, in El Alto, Bolivia (in Spanish) http://www.pensamientocritico.org/rauzibe200905.htm

In my In These Times article, I mention urban self-organization in South Africa. My main source was focused on Symphony Way, Capetown: “Anti-Eviction Struggle of the Squatters’ Communities in Contemporary South Africa,” the paper presented by Daria Zelenova at the “Hierarchy and Power in the History of Civilizations” conference, the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 2009.

You can also check out this article from Patterns of Commoning

and this website of one of the organizations of shackdwellers fighting against evictions or for increasing the resources and solidarity available to these self-constructed neighborhoods

More on fighting for the city, from “Ecosystems of Revolt”

Decentralization vs. Colonization:

Existing against the State, with the ecosystem, and with few or no internal hierarchies is a common feature of many Indigenous societies.

Decentralized networks of stateless Indigenous communities are a vital element in stewarding and caring for the Amazon, which is one of the most complex ecosystems on the planet. The Amazon is not pristine, if by pristine we mean a wild place untouched by humans. Actually, it’s more of a garden in which humans are the gardeners. But here’s an important distinction: Amazonian communities take an ecocentric rather than anthropocentric approach to gardening. It is not their property or stockpile of resources, it is the home they form a part of.

“Indigenous agricultural practices sustainably managed the forest's natural biodiversity for millennia”, at least 5000 years, across a huge geographical region with ten million inhabitants speaking hundreds of languages https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/remote-amazon-region-study-shows-indigenous-peoples-have-practiced-forest-conservation-millennia-180978038/ To clarify on the complexity of these interlocking societies, 330 languages were documented in the Amazon post-colonization, and these languages were from 25 different language families along with fifty isolates. There could easily have been 400-1000 languages spoken across this huge region before colonization. Despite the lack of a common language, millions of people spread knowledge, tools, techniques, technologies, and culture across thousands of kilometers, cultivating and strengthening a shared ecosystem, creating and sharing abundance, keeping out external states, preventing the emergence of states from within, with full decentralization and autonomy. Every community was allowed to develop independently, with their own culture, their own language, their own approach to survival. Some communities fed themselves with hunting and gathering, others with aquaculture, others with nomadic horticulture, others with frequently shifting agriculture, others with sedentary agriculture.

(With far less linguistic and cultural diversity—around 200 languages all belonging to a single family, plus a couple tiny language isolates—Europe under the control of competing states has been the site of poverty, famine, deforestation and ecocide, and most of the bloodiest wars in human history. That, in a nutshell, is the State.)

Indigenous people in Amazonia are not ignorant, innocent, or pure. They have had knowledge of states for over a thousand years, long before the European invasion, and they have chosen to resist, refuse, and overthrow them. Western Amazonia had a hierarchical civilization of cities with religious-ceremonial centers (a key feature of many early states) that was inhabited between 200 or 500 and 1400 CE. According to local oral histories, this state or proto-state was voluntarily abandoned or overthrown, similar to the Tiwanaku civilization in the Andean highlands.

Indigenous people in the Amazon have been key to changing the colonial view of this region as a scarcely populated pristine wilderness populated by isolated, ahistorical, and ignorant tribes. Amazonian peoples today still consciously and carry out the same intelligent practices that cultivate and maintain the rainforest that they have for 5-12,000 years, for example their techniques to produce the black earth the region is known for. Professional scientists have only “discovered” this recently when they tried the novel approach of speaking to the inhabitants of the land. https://rainforestfoundation.org/the-ancestral-forest-how-indigenous-peoples-transformed-the-amazon-into-a-vast-garden/

Indigenous resistance is a model for rooted networks:

Much of the most effective resistance against the forces destroying the planet have come from continental networks bringing together multiple traditional Indigenous communities and peoples, without centralization. Some of that resistance is discussed in the report “Indigenous Resistance Against Carbon,” which focuses on efforts to stop fossil fuel expansion in North America, the documentary “2 de Julho: A Retomada,” which looks at Indigenous resistance in Brazil, Klee Benally’s No Spiritual Surrender, and Chapters 3 and 4 of The Solutions Are Already Here.

Here are links that give more background on Indigenous societies I reference in the original article.

*On the State and the abandonment of the State in the history of the Maya: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caste_War_of_Yucatán

*On the Amazigh and the Kabylie Uprising, https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/matouf-tarlacrea-echoes-of-the-free-commune-of-barbacha

*On the Anarchic Practices of the Mapuche, “With Land, Without the State” https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/anonymous-with-land-without-the-state-anarchy-in-wallmapu

*The Art of Not Being Governed looks at many examples in Southeast Asia, uniting them into a systemic analysis

*The Dragon and the Hydra follows a broader pattern of rank-and-file veterans of the Black Panthers who moved towards more anti-authoritarian or explicitly anarchist strategies. In this text, Russell “Maroon” Shoatz uses examples of Black and Indigenous resistance across the Caribbean to claim a lineage of struggle and demonstrate the advantages of decentralized and anti-authoritarian resistance

*Modibo Kadalie embarks on a similar project, looking at self-organization by maroon communities in Fort Mose and the Great Dismal Swamp, in Intimate Direct Democracy

*A documentary on the MST in Brazil: https://kolektiva.media/w/tfpR2XBCBJFnxeR48KzfT9

Decentralized networks are how we survive disasters:

Anarchist principles of Decentralization, Mutual Aid, and Solidarity also prove their effectiveness when state authority breaks down in major disasters

Check out scott crow’s Black Flags and Windmills, about solidarity and survival in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, when state power collapsed, state interventions largely focused on moving prisoners (or abandoning them to their deaths) and shooting looters, and capitalists salivated over “gentrification by God”. In those circumstances, it was only the solidarity of neighbors—of rooted networks—that kept people alive and even made life better.

Dean Spade’s Mutual Aid is a highly praised book that does such a good job of examining the mutual aid as a practice of survival amidst pandemics, deadly hurricanes and wildfires, or “the ongoing horrors of mass incarceration, racist policing, brutal immigration enforcement, endemic gender violence, and severe wealth inequality. As governments fail to respond to—or actively engineer—each crisis, ordinary people are finding bold and innovative ways to share resources and support the vulnerable.”

A specific case study regarding the impact of Hurricane Helene in Appalachia can be found in “The Eye of Every Storm”

In her book, Rhiannon Firth provides a studied analysis of Disaster Anarchy: Mutual Aid and Radical Action

Decentralization and self-organization are always there in the shadow of the State. Nowadays, they show up most dramatically when state power and state infrastructure collapses. Think about major hurricanes, floods, and wildfires: who carries out the vast majority of rescues, who distributes the vast majority of resources for survival? Overwhelmingly, it’s regular people organizing themselves spontaneously. But we can also see this truth in much more mundane circumstances. How many of us have worked in a job where there was an official structure that described how decisions were supposed to be made and how the work was supposed to be organized, and there were bosses and managers with more power and higher incomes, but frequently—maybe even constantly—those official structures didn’t actually work and the regular workers had to figure out on our own how to make things function.

The State can’t exist without our constant capacity for self-organization and initiative. On the other hand, we can exist without the State.

They need us, we don’t need them:

States systematically make use of decentralized infrastructures and practices to shore up its own limited resilience and make up for the inefficiencies and bureaucratic stupidity of centralization

Sometimes, this looks like governments co-opting, funding, and regulating global networks that had already organized themselves, like the postal service, libraries, scientific research journals, the internet, maritime networks, and more.

In their March 31 2025 newsletter, “Signalgate Caused Signalgate,” Emsenn describes the 2006, interagency and international series of war games, Operation Cyber Storm, “which simulated coordinated attacks on critical infrastructure: power grids, transportation systems, communication networks […] Cyber Storm scenarios grew to include misinformation campaigns, public panic management, zero-day exploits, and supply chain interference.” How did these hardened government agencies, with security budgets larger than the economies of most countries, hold up under adversity? “Participants frequently failed to communicate across silos. Classification slowed response times. Jurisdictional confusion reigned. Most crucially, participants often resorted to backchannel communications when formal systems broke down.”

Emsenn is looking at how both total surveillance and intelligence leaks become routine, which is an important lens. We can also take our analysis in a different direction: Cyber Storm is yet another demonstration of how the security practices of governments and bureaucracies are cumbersome and vulnerable to breakdown, and the only thing people in government can do in the face of collapse is to learn how to operate through informal networks, which are much more resilient, expedient, efficient.

Another example, that we can draw from the manuals of covert warfare, is how the world’s leading intelligence agencies and special forces branches train their units to operate using remarkably unmilitary methods, methods that might recall the basic features of anarchist guerrilla cells and affinity groups in a riot: work in small, largely nonhierarchical teams empowered to make their own decisions and change most of the specific details of their mission in order to adapt to circumstances and move with the chaos. This is because of a widely studied but largely downplayed feature of hierarchical militaries: how inefficient, cumbersome, slow, and maladaptive they are.

In other words, the military chain of command or some authority figure in an intelligence agency will give a basic mission or goal to a group of operatives or special forces team, and then those operatives and teams function outside of the chain of command, with a far more effective, far more anarchic methodology – albeit one in service of statist goals.

This practice is illustrative of a wider principle which is one of the State’s best kept secrets: while we can survive just fine without states, states can’t actually function without the intelligent, resilient, effective decentralized networks that actually make the world go around. The visible part of the State’s structure is formal, ranked, obedient, bureaucratic, demarcated, rigid. But the State needs to be able to capture pre-existing networks and practices that are informal, spontaneous, self-organizing, adaptive, flexible, and impermanent/always-changing.

The hierarchical structures are part mythology—homage to the religion of power—and part necessity, the way the State is able to access, extract, concentrate, and centralize the knowledge and wealth of the world. But nine times out of ten, if you look at how the knowledge and the wealth are actually created and passed around, you’ll find decentralized networks in play.

Here are some books and articles that can be useful for further reading:

Jimmy Dunson ed., Building Power While the Lights Are Out

Fuerza del Fuego: la lucha por la autonomia de Cherán K’eri

Survival International ed., Decolonize Conservation: Global Voices for Indigenous Self-Determination, Land, and a World in Common

Klee Benally, No Spiritual Surrender: Indigenous Anarchy in Defense of the Sacred

Modibo Kadalie, Intimate Direct Democracy

John Severino, “With Land, Without the State,” “Evo’s Highway,” “The Other Gods Were Crying,” and other articles and interviews by John Severino

me, Worshiping Power & Anarchy Works, chapters 4 & 5 of The Solutions Are Already Here

Steven Johnson, Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software

Both of the final two books, below, are written by professional anthropologists. They’re really important books, but they need some caveats. Anthropologists often provide a theoretical lens for social mapping in so-called post-colonial societies or societies on the global periphery, and this mapping is often useful to, and even paid for by, institutions engaged in counterinsurgency. This is especially the case with James Scott, though I’m unsure to what extent Scott was aware of this.

For his part, Clastres was doing important theoretical work in his context—European academia in the middle of the 20th century—taking on both Marxist and liberal orthodoxy which believed in the inevitability of the State and the value of progress. Clastres helped show that stateless societies are not pristine, innocent, ignorant, or relics of the past. They are intelligent societies with a history and with cultural strategies for protecting their autonomy. They aren’t societies without a state, they are societies against the state. Beyond that valuable work, Clastres unquestioningly reproduced many of the patriarchal and intellectual values that were normalized in the professional classes of 20th century France.

In any case, here they are:

Pierre Clastres, Society Against the State

James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed

Thanks Pete,

great news letter with lots to follow up on.

While it's obviously built differently than the old guard like Britannica, Wikipedia is highly exclusionary & reproductive of oppressive heirarchies internally as well as within colonial capitalist societies.

https://types.mataroa.blog/blog/wikipedia/