I test the end of the iron rod sticking out of the glowing furnace. It’s gentle. I grasp it and slide my hand forward until I start to feel the heat, just like he taught me. On other stages of this work, I’ll need to grip it with the tongs, but for now it’s just so, vulnerable, close, flesh on iron.

I pull it out of the 1100C furnace and pivot to the anvil behind me. Arm at 30º, tip of the rod just up to the lip at the anvil’s edge, hammer arm coming down at 45º. Pound, twist, pound, twist, pound, twist. Just like he taught me. Slowly, surely, the rod transforms, sharpening into a pencil point.

The glow is gone. Heat, he says in my ear. I turn and slide it gingerly back in the fire.

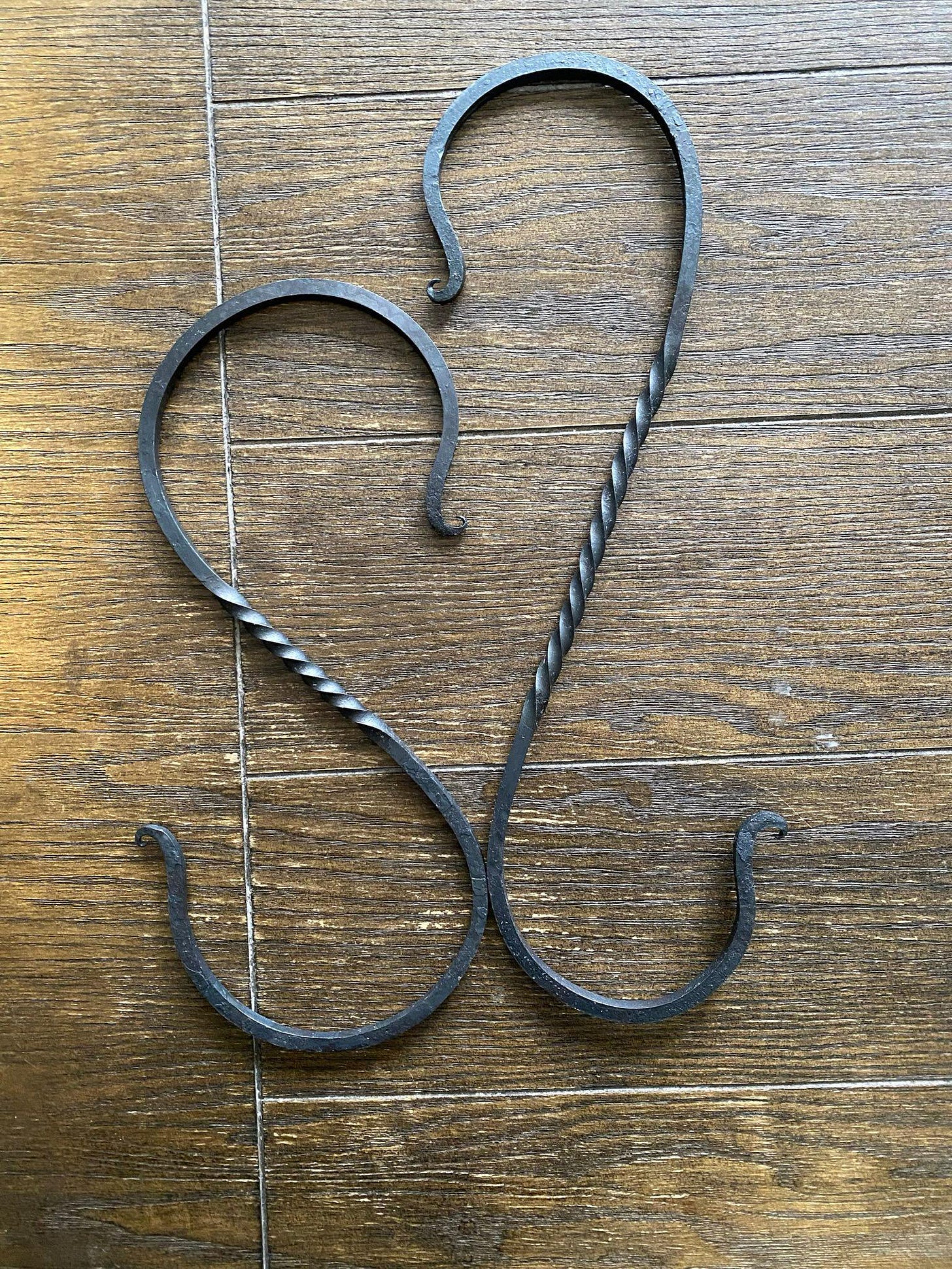

I’m here to make this rod into something else: a symmetrically curved S-hook for hanging flower pots. There is a time in the occasion—this blacksmithing class will not last for ever—and there is a time in the heat. When the glow is gone, the moment for fine work is passed. No pencil points. And while it is still hot but not glowing, only firm blows to coax the rod back to straight where missed strokes led it awry.

Hold your arm out, stare straight down the piece, notice any unintended bends or warps. Lay it flat on the anvil’s back, rotate it until the bend is hump-up. Strike it hard. Then back in the fire.

There is also a time in the metal, though I’m not sure if we can know it. As stone in the earth’s crust. Smelted and cast as a bar. If we hadn’t pulled it out of the box, it might have lasted centuries in that form, slowly rusting, oxidizing, turning into another version of itself.

I don’t need to change it. I could let it change on its own time, much longer than my own. I could pull it out of the furnace and just watch it glow, slowly slowing, pale orange down to dull red, finally back to black.

I think it might like my attention, though. Might enjoy teaching me about itself. Could, perhaps, appreciate holding up flowers for a year or a hundred years. A short time for a piece of iron.

I’m certainly enjoying this blacksmithing class. It was a brilliant birthday present for me from my boo. Not only am I a medieval nerd and amateur fencer (saber, kendo, and broadsword). I’m also a fantasy writer with a few manuscripts inching towards publication. And often it’s the detail of that unseen research that adds an ineffable sort of texture and allows an imagined world to truly resound.

Above all, I love a thing well done, I love the artisanry. Just take the anvil. Anyone today who wants to forge by hand will probably be using a London Pattern anvil, a design that is nearly two hundred years old. And the major features of the London Pattern anvil can be found in many illustrations of anvils from 800 years ago or more.

Think about that for a second: a piece of technology that is collective property, that evolves in a decentralized manner, but that can retain its validity and effectiveness for 200 years, for 800 years. None of the designers and developers who provide the creative thinking for the cutting edge economy today can take that much pride in their work. I doubt how many of them actually imagine a kind of quality that is not disposable.

Fortunately, while I’m in the smithy, I’m not thinking bitter thoughts about capitalism, I’m just having the time of my life as R and I take turns on the anvil. We learn how to sharpen the tips, how to coax a sharp point into a curl, how to wrap the rod around the anvil’s horn to create a broad curve, how to twist a clamp to make a spiral.

My elbows are causing me a fair amount of agony. The hammer isn’t heavy, and we don’t have to wail on the anvil like they do in the movies, but this second cycle of chemo is giving me pretty bad joint pain. Fortunately, there’s one hammer, one anvil, so R and I take turns. Most of all, the craft is fascinating, all the things to learn, all the rich layers of technique and history we’re just getting a glimpse of.

Our instructor tells us not to worry about mistakes. Warps, twists, galloping. When we direct the force of the hammer against the iron, we need to understand what it needs to do with that tension. Once we understand where it’s going to want to go, we can clear the path and accompany it to the shape we’re looking for.

I saw this most clearly not when the hammer was in my own hand, but when I was at R’s side, perpendicular, staring longwise down the anvil as she practiced the same movements I had struggled with. Seeing her, the anvil, and the hammer, watching the rod respond, happy or resistant, I could see what was obscured when I was in the thick of it, and I could better understand the techniques I was trying to learn.

The mistakes are inevitable. And they can be corrected. You just look straight down the length of the rod, identify them, put the piece back in the furnace, and be patient. Once you pull it out again, glowing, incandescent, you’ll have another chance to work out the warps, to straighten the bends, to finesse the curves. Not an infinite chance. The metal will lose its glow, the moment will pass. But the furnace is still there. You’ll get another chance.

Incandescence, so often, becomes a symbol for rage. The white heat of anger. As I’m learning to smith, though, I’m understanding that glow as a cue for patience. The metal is not infinite. You cannot keep hammering it after it’s gone cold, you cannot hammer it counter to the direction it wants to go in and expect some other result. And even if you’re trying to do it right, sometimes you will hammer it wrong and it will buckle, bend, or blunt.

But if you put it back into the fire, if you give it time, soon it will be glowing again. And if you stare a moment before rushing back to the anvil—if you refuse to see time as something that is always escaping you—you will see that through its incandescence, the metal is singing: you can learn how to do this better. We can become anything at all.

This is not a metaphor for life or love. Iron can take a beating we should never have to. But if we move through the world attentive to the things around us, try to see their needs and hear their wants, we might discover some really useful techniques, tools for the ages. Like an anvil or patience. And we might even unfold a little of the beauty that is at the heart of everything.

Want to help improve the odds of me getting my other fiction projects published? Share and review my debut novella, Hermetica, or ask bookstores and libraries to carry it!

Imagination Will Save the World

So first a little surprise announcement: this isn’t exactly a guest column. I’m Alan Lea. I’ve actually been writing fiction—largely fantasy and scifi but also stories outside the genre—for longer than I’ve been writing my nonfiction screeds. All the way back in elementary school, telling stories felt like a biological need to me. It wasn’t until high s…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Surviving Leviathan with Peter Gelderloos to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.