I sat down to prepare the talk I have to give this afternoon about a friend who died in the struggle. But my mind is flighty, my breath shallow, shadows of sadness and anxiety, so first I’m writing to you.

The birds around our lakes have declared that today—exactly one month after Groundhogs Day—is the beginning of spring weather, spring behavior, spring songs. In the span of one week we went from days below freezing to short sleeve weather at 18º (64ºF) and then back below freezing, dropping in a single day from a balmy morning to a freezing afternoon.

The crocuses shot sunward like soft little spears, then cast their heads downward, but they’re still hanging on, and despite the lingering cold the birds have decided: they’re not convinced. And today they announced as much with a sudden explosion in repertoire, cardinals and robins in particular adding whole new varieties of song to the warbling of woodpeckers, the chatter of sparrows, the shriek of jays, the chirp of starlings, as passing raven couples and hunting hawks battle the local crow family for position in the tall trees overhead. And at our little lake, the very first morning of the year, a redwing blackbird erupted in song. He flew clear across the lake, abashed, when he heard our excitement, but he always warms up to us later in the season.

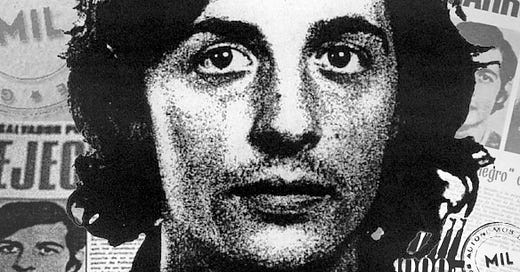

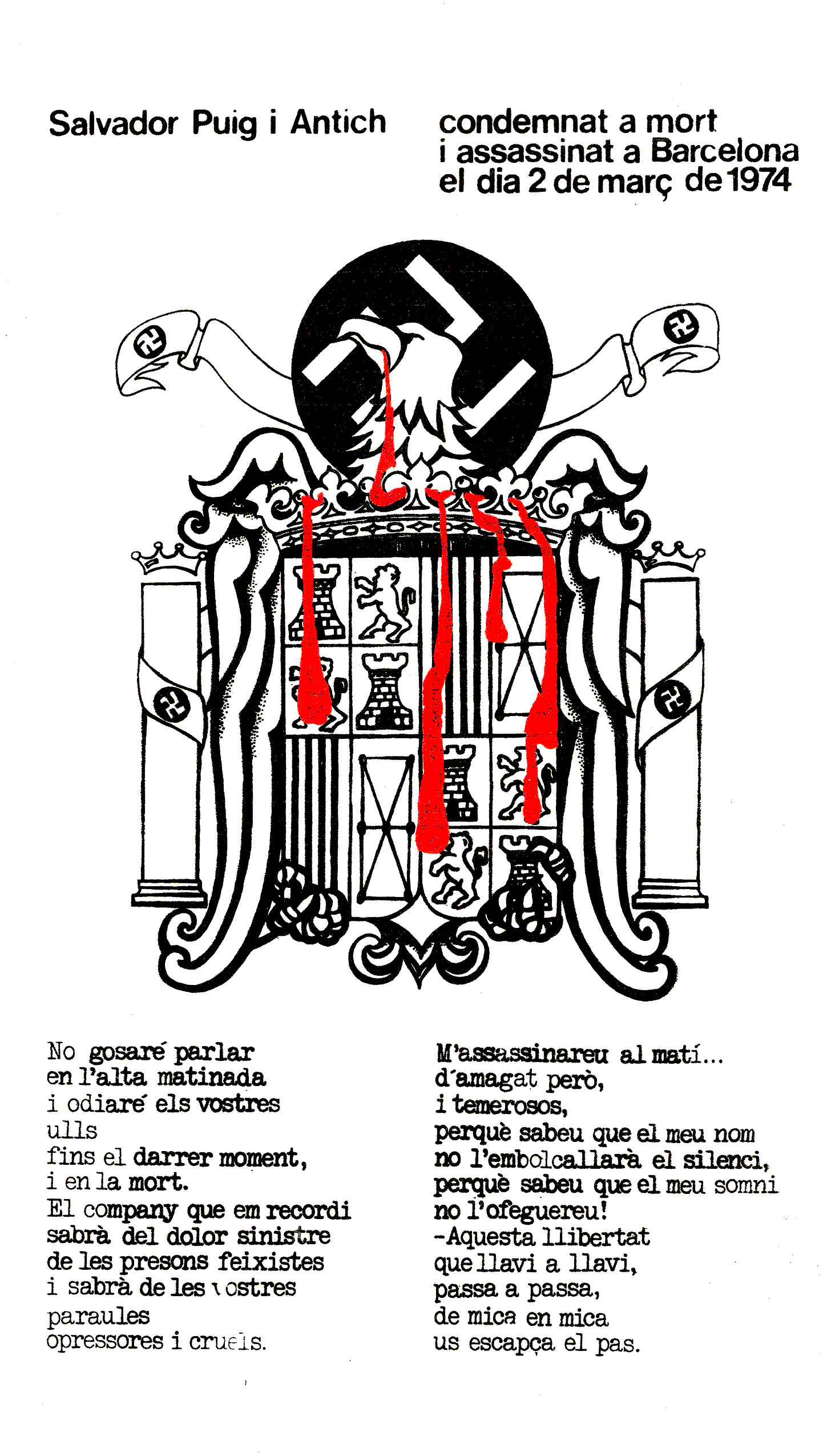

March 2nd. Fifty years ago today, Salvador was executed by the Spanish state, his throat crushed with a garrote. The cops had swooped down to arrest him and another comrade, a cop got killed. Salvador was a close friend of several of older friends of mine in Catalunya, who participated alongside him in the struggle against the dictatorship. A struggle, Ricard’s voice rings in my ear, against capitalism: dictatorship and democracy have each been ways to manage capitalism.

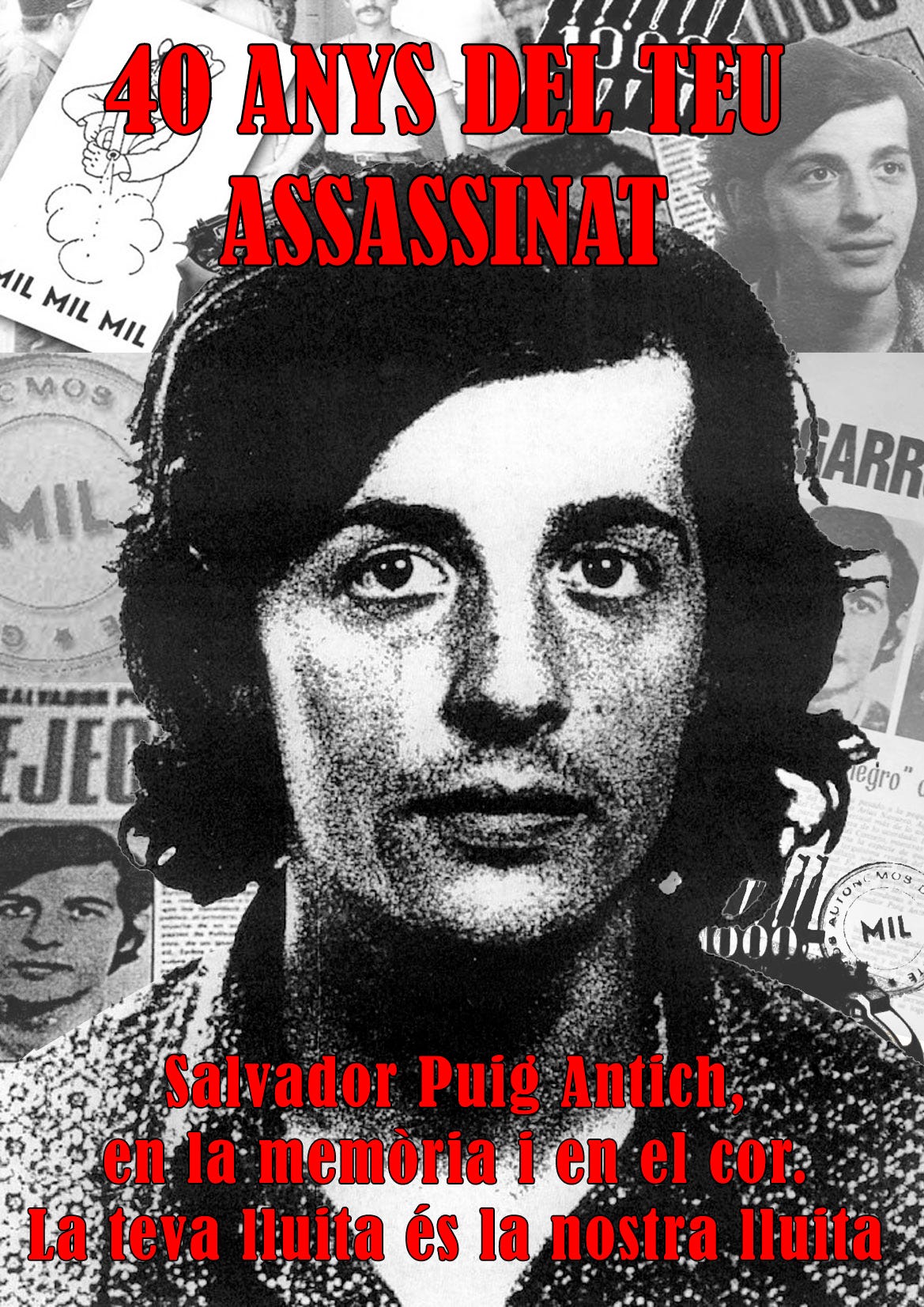

I think actually the first thing Ricard and I worked on together was a big event we put on in Barcelona on the 40th anniversary of Salvador’s death. Ricard was sad to find out that with my ongoing treatment, there’s no way I’d be able to make it for the huge commemoration they’re doing this year, but I promised I’d put something on in the US. Per la memòria històrica, for historical memory, a concept that is slowly trickling back into anglophone radical movements, largely through osmosis from Latin America and the Mediterranean. The kind of memory that would teach us useful things about democracy, antifascism, armed struggle, survival…

But today I’m having a harder time articulating those lessons, the meaning of it all. I’m just remembering little stories. The corner in Guinardó (one I’ve passed a thousand times) where members of the MIL would have secret meetings with other cells, with delegates from striking factories, the apartment window where the lookout would be posted… the stories of kids in El Clot playing ball in narrow streets (since widened by gentrification), insulting passing cops and running away. Ricard’s first memory: a burning streetcar on the high road during one of the first strike actions under the dictatorship. Actions a few years later he and his friends would be participating in directly.

I also keep getting flashes of my own memories, memories that first played through my own eyes, people I knew personally and who I’m remembering these days. Just last month, two anniversaries went by for me.

I remember my grandfather, teaching me to shoot, to fish, his emphasis on safety, on respect. Getting us all dressed up as pirates, his Bert and Ernie impressions. Then later, I remember our angrier and angrier arguments over my evolving political stances. Thoroughly patriotic, he had enlisted in the military right after Pearl Harbor. Through the Cold War he grew more critical, but when he left the military he became a priest.

He thought my position on the invasion of Afghanistan was treasonous. But later, by the second invasion of Iraq, we didn’t argue any more. I was learning how to respect someone for their beautiful heart, no matter how different their values were from mine, and he took me seriously enough to learn what it meant that I was an anarchist. In one of the last conversations we had, he said he’d tried the best he could in his life, and he wished me the best in my own attempts. (And I know that was meaningful, given how a few years earlier he’d said he would stand on the side of his government, even if it meant shooting me, if I ever participated in a revolution.)

A week earlier, the 13th was the anniversary for Aragorn! About as different from my peepaw as someone could be, Aragorn! was the trickster god of the North American anarchist space for over a decade. I remember the twinkle in his eye as he was expounding some position, unsure if it was a provocation, an experiment, something he firmly believed. I remember the viciousness of the partisan squabbles in the comments section in Anarchist News, and how gentle they were in comparison with the people who tried to cancel Aragorn!, or in comparison with Twitter. Back then it was easy enough to say, the struggle is not in the comments section on A News, but nowadays there aren’t so many people who distinguish between virtual space and meatspace, or who even fully inhabit the latter.

I think about how many of my positions Aragorn! mocked, and his later positions I never got to try to argue him out of. But despite that satirical smile, that glinting eye, despite how I was a wholesome hippy next to him who naïvely believed in concepts like movement and struggle, he and his closest friends and partners always supported every project of mine that could find a home or an audience on the infrastructure they built. In that sense, with that generosity—I could say, to provoke his little ghost, wherever it is—he believed in the movement more than most of us.

(I can already hear his rebuttal, and the distinctions he’s making are valid, and I guess the kind of provocation that drives you to articulate yourself is a useful kind indeed.)

Most vividly I remember when he visited me in Barcelona, both of us bobbing in the sea, and the advice he offered for dealing with some folks who were harassing me at the time.

“Outlast them.”

And the truth of it gave me hope, because cannibals always run out of friends, and there’s not much we can do in this world without friends. But that hope also dies sometimes. There’s something poisonous in the soil, and every couple years a new batch of cannibals are born, and they’re more vicious than the last.

So I start thinking again about survival.

It was the beginning of a winter when a friend from prison, Greg, died. The only other anarchist I met during my time on the inside. He survived about a dozen years and then died within a year of getting out.

And that memory brings me to other memories of loss, because I had left the States when I found out he’d died. I wasn’t able to share it with anyone else who knew him. That whole winter I spent in Ukraine, making friends with people whose lives have been turned upside down more recently, by diaspora or warfare. Some of them I haven’t heard from recently, and I worry.

Other times, hearing can be worse. When three anarchists were killed outside Bakhmut on April 19 last year, we knew pretty quickly that one of them was Cooper, a friend of several friends in the haven where I’ve been living lately, and always a calm presence at our social center. It took a little longer to realize that Dmitry was Dima, a comrade I’d been fortunate to share a few important occasions with on trips east. And a few months after that, in the middle of a conversation at our social center I realized I was talking family of the third of the group, Finbar, who had come to town to connect with Cooper’s family and friends.

I don’t want us to lose any of them. But that’s on us. The work of remembering is on us.

If you’re interested, here’s a book Ricard put together of writings by and about Salvador Puig Antich and also the clandestine struggle he participated in, against what turned out to be the longest-lasting fascist dictatorship in the world.

https://www.akpress.org/salvadorpuigantich.html

And here’s a copy of the illegal poster Salvador’s friends put up in the streets in the hundreds and thousands, printed and distributed through their own clandestine networks, back in 1974 when their friend was killed.

We’re still here. Let’s take care of ourselves.

Thank you as always for your beautiful and charming writing. I always get excited when a little notification pops up saying you have a new essay. I hope you are feeling well, and much love to you and your loved ones.

just a note: this was the 50th anniversary of Salvador's death, while the poster featured in the article is from the event we put on ten years ago, which is why it says "40 years"