This is really embarrassing, but when I was a kid two of my favorite movies were Legends of the Fall (1994) and Braveheart (1995).

Much scarier: this is my third attempt at writing this essay. I derailed myself the last two times with dense layers of abstract cultural critique, one of those times even diving into avoidant tangents about James Horner’s compelling scores, Brad Pitt with long flowing hair on horseback, and how Braveheart substituted perspective tricks and shaky camera work for any tactical realism about how pre-firearms battles were actually fought.

This essay is not about film-making. It’s about the relationship between masculinity and trauma.

I’m trying to start with these movies because of how they can help us see certain patterns in patriarchal masculinity. Both are atrocious, politically. One in a conservative way, the other in a progressive, white savior-y way. The Mel Gibson production shows us a very traditional, reactionary masculinity. The Edward Zwick film presents what at the time was a much newer, progressive masculinity. The emotional dynamics and motifs that show up in both of these movies are what I find most relevant.

In both movies the protagonist loses loved ones to violent deaths (his wife and younger brother in Legends, his wife in Braveheart). In both movies, the protagonist endures severe beatings and torture. (In every case, male characters are the ones inflicting the violence.) In both movies, they take their brutal revenge. In Legends, revenge even serves as the basis for what’s meant to be a touching scene of father-son bonding and redemption: don’t fuss with talking about your problems, just prove you’re on the same team by killing some common enemies together.

And in both movies, men cry. In Legends of the Fall it’s the protagonist (Brad Pitt), and in Braveheart it’s the protagonist’s best friend, though Mel does dissociate and get a little teary eyed after suffering an unexpected betrayal. For his part, Brad spends a third of the movie dissociating, red-eyed, and engaging in pointless and brutal quests.

I was only able to find one mainstream movie before Legends of the Fall that depicts adult men as protagonists or heroes who cry (Schindler’s List, 1993), unless you go all the way back to It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), and other progressive films from that time period.

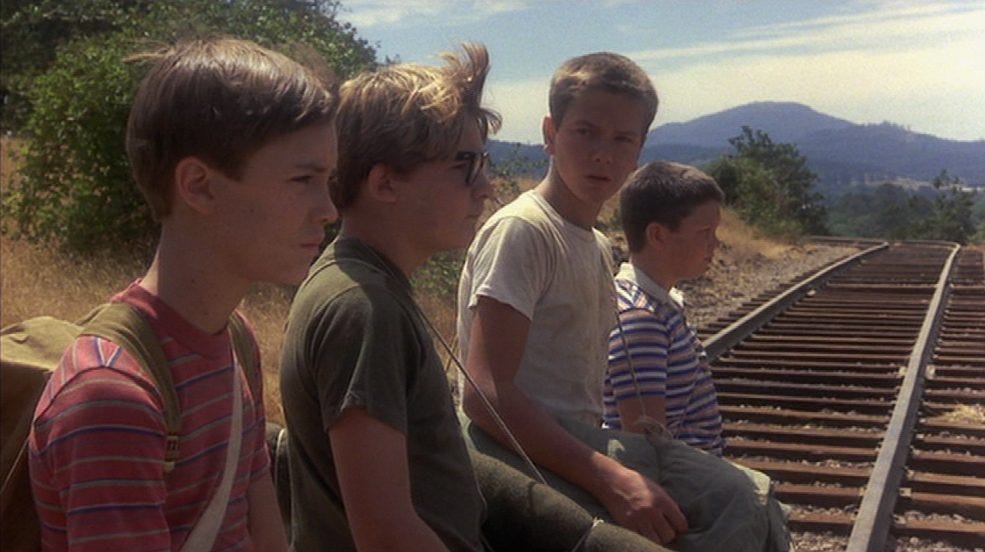

But in the ‘90s, patriarchy experienced a minor shift. It was preceded by a few poignant films from the ‘80s that show boys or teens crying, like Stand By Me (1986) and Dead Poets Society (1989). In both of those, the characters are dealing with questions of neglect, abuse, trauma, and suicide—situations that weren’t often the topic of movies in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and early ‘90s. Of the four child actors from Stand By Me and a fifth actor who was a close friend and co-star from another movie, at least three experienced sexual abuse as children. All three of them developed serious drug problems, two of them died very young, and the third was himself accused of abuse as an adult.

Hollywood changed and everything stayed the same. Patriarchy changed, and everything stayed the same.

Patriarchy can allow boys and men to cry.1 It can acknowledge we experience trauma. But an abstract awareness of being hurt or traumatized is not the same as healing.

I want to be clear about something. I think it’s undeniable, or it should be, that hurt people hurt people. However, that in no way means that every time a person hurts someone else, it’s because they’ve been hurt in the past and they just need more love. Cops and millionaires don’t harm people because they didn’t get enough love as children. They harm people because they get paid to, and because they enjoy it or are very good at ignoring it. We can call that “actively harming others in exchange for social and economic benefits.”

Then there’s another form of harm related to privilege, entitlement, and marginalization. I think it works like this: anyone can be socialized to accept harm against certain categories of people. In those contexts, some people intentionally target members of those categories, knowing they can get away with it, and others help normalize the harm by looking the other way, no matter what their personal feelings are.

All of those are real problems that define many of the contours and lived experiences in our society.

What I want to focus on here is how people in a lot of pain are likely to hurt others if they don’t commit to healing, and how patriarchy is a machine that thrives on unhealed trauma, getting people to reproduce harm and aim the pain and anger they feel laterally and downwards.

I think one thing I subconsciously liked about those two movies when I was a little kid is that these tough, heroic guys could have really horrible things done to them, they could experience a lot of pain and anguish, and yet they could retain agency over their lives. All they had to do was push the trauma down and respond with anger, vengeance, and dissociation.

Long before I knew the word “trauma,” I was looking for a method to do just that – reclaim my agency despite some pretty horrible things I lived through in kindergarten and at home. By 3rd grade I was cutting, and sometime between 4th and 5th I started seeing a therapist. He was very nice. I never told him about my heavy thoughts or what I was going through, because I didn’t want to burden him, and I never told anyone that this particular method of therapy (creating a “safe space” for me) was doing fuck-all for me, because I didn’t want to hurt his feelings.

I didn’t need a safe space, because there wasn’t any real safety for me where I needed it most. I certainly could have benefited from unloading and expressing all those ugly, terrifying, gut-wrenching feelings, but I wasn’t going to get to a place where I could do that in a periodic one-hour session, given all the other pressures, incentives, messages, and models in my life urging me to keep everything bottled up. Add the fact that when certain things happen to you at a really early age, literally the only thing your mind is capable of is dissociating and compartmentalizing. And if that’s what gets you through it initially, that’s going to be a tool you’ll want to keep close at hand for the rest of your life.

What I needed was to be challenged. I think anyone who learns unhealthy coping mechanisms needs that in one way or another: to see the walls they’ve put up, to see what’s behind those walls, to accept that it’s not their fault, to learn how to let those messes compost rather than walling them up; to hear the stories they tell about their life, to understand where those stories came from, to validate what’s true about those stories, to recognize how those stories hurt them or hold them back, to see what’s left out by those stories, to learn how to write better stories; to identify their coping mechanisms, to explore how those mechanisms affect others, to feel the pain they cause in others and the pain others might be experiencing for completely other reasons (i.e. the “it’s not always about us” principle), to commit to empathy, and to take responsibility for how they show up in the world.

I think in our society, nearly everyone reproduces harm with at least some frequency. I think unless they’re extremely lucky to grow up in a family or community with a great deal of accumulated emotional wisdom, those who experience oppression or some other scarring situation2 nearly always learn coping mechanisms that lead them to act harmfully to themselves and others – either others in their own peer group, or people lower down the social hierarchy than themselves.

That’s one of the things that keeps a society like our own, based on multiple intersecting, entangled forms of oppression and extraction, functioning. The farther down you are, the more oppressed you are, the more reasons you have to revolt, but you’re simultaneously exhausted, traumatized, in constant survival mode, and you’re taught to blame or attack other members of your own group or the members of another marginalized group.3

This dynamic plays out regardless of gender, though so much of the content of traditional gender is like an instruction manual for how feminine people and how masculine people should perform their selves in traumatizing experiences. Maybe for feminine people, it’s a continuum that we’re taught is supposed to run from taking the abuse stoically, like it’s one’s lot in life to be a victim, all the way to having a “hysterical” break down (“hysterical” itself being a gendered, misogynist word).

For people who are supposed to emulate masculinity, the continuum ranges from acting like a bad situation doesn’t affect you in the least, water off a duck’s back, to taking violent revenge on whomever you identify as the enemy.

I think traumatic experiences are or can be a fundamental element of patriarchal masculinity. But there’s not much awareness of that, primarily because so few cis men do the vulnerable work of exploring, healing, and teaching about trauma; we either brush it off like it’s not there, or we use it as an excuse to justify harmful behaviors we have no concrete plans of addressing or changing. Secondarily, I think it’s because of superficial understandings of what “privilege” actually means in real life, and because of the trap of superficial binaries.

(Our society, without a doubt, uses binaries as a tool of ontological and epistemological oppression, and binaries are by their nature reductionist. We correctly identify some of the binaries at play, but often make the mistake of taking their reductionist truths at face value; we take less time looking at the complexities these binaries obscure. E.g. our society clearly deals in terms of “male or female” and clearly assigns certain values, behaviors, and expectations to each. This is oppressive and also reductionist, and it’s good for us to call this out. However, we also simplify reality when we expect the norms or ideals of patriarchy to accurately reflect reality on the ground.)

Here’s an example: college fraternities and especially the military are two patriarchal institutions that have long provided a rite of passage into manhood. In these rights of passage, it is standard for one rank of already-men to physically, emotionally, and even sexually abuse a lower rank of almost-men. In these rituals, those in the lower group are expected to encourage one another to accept it and celebrate it, and those in the higher group are expected to perform enjoyment while inflicting abuse. The end result is induction into an institution whose members need to be able to systematically use physical, emotional, sexual, economic, and lethal violence against others.

Cruel institutions will always spark resistance. At a certain moment, patriarchy needs to be able to pivot if more obviously brutal forms are generating a destabilizing amount of resistance (or if the systems of accumulation in place can profit off a gentler model of patriarchy).

Specifically, patriarchy sometimes has to acknowledge trauma without neutralizing it, without losing one of the most valuable motors for reproducing patriarchy.

So, trauma can enter the vocabulary. We can realize it’s a part of our society. Certain demographics with the right resources and compatible responsibilities can even spend their free time healing from trauma, as long as their approach is individualistic.

This is where the culture industry, Hollywood, can play a valuable role, representing a feature of oppression in a way that is critical or progressive, without subverting the foundational power dynamics.

With a good actor, the right musical score, and evocative camera angles, trauma can even look romantic.

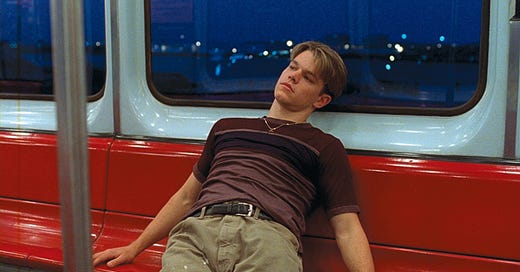

Cue Good Will Hunting (1997). Another movie with a man who cries, who brushes off trauma or channels it into violence against others. In its defense, I want to say I think the movie is well intentioned, its portrayals are respectful, Robin Williams is a sweetheart, and Elliot Smith makes me want to cry.

(Smith, who wrote the song that plays at the movie’s finale, also was sexually abused as a child, suffered from depression, had drug problems, and stabbed himself in the heart after an argument with his partner, six years after the movie was released.)

Good Will Hunting goes farther than other mainstream movies of its time that deal with traumatized men: it takes place in contemporary, working class Boston, rather than in a distant or heroic time period; when Matt Damon beats some guy in the street to a pulp, the director means for us to see that as disturbing rather than tragically heroic; it gives a fairly accurate portrayal of masculine sociality – a bunch of dudes who have one another’s backs and enable their harmful and emotionally avoidant behaviors; and it gives us a story in which Damon’s character admits to being abused as a child and has to go to therapy in order to change.

If the movie is indeed well intentioned, it fails in all the ways it reproduces traditional gender expectations or obscures what we need to do to deal from harm even at the smallest interpersonal level.

Damon’s character starts a relationship with Skylar, played by Minnie Driver. From the beginning, he’s charming, emotionally avoidant, and dishonest, using extreme compartmentalization to hide his current poverty and his upbringing in a series of violent foster homes. When he finally acknowledges the abusive background he has been hiding, it’s because Driver’s character keeps asking about his family and his past. She does it in a gentle way, in a sweet way, and at one point Damon snaps, begins shouting and explaining things with violent language as though his reaction is Driver’s fault, and he begins punching the wall right next to her head.

Then he storms off, shields automatically up, and barely reveals any emotions at all in the following scenes.

Driver is portrayed sympathetically as she sobs in that scene and in her couple other appearances in the movie, but far and away the movie is constructed to normalize what she is going through and to focus all empathy on Matt. For her, it’s sad, it’s tragic, hopefully he’ll come to his senses and rescue her (not rescue her from abusive relationships, but rescue her from the tragedy of losing her romantic love, the tragedy of being a cute gal without a boyfriend). For him, he’s the wounded creature who has a story to tell, a narrative arc to complete, he’s the one who needs resources and patience. And throughout it all, he looks good, if not heroic then certainly romantic.

He gets the resources he needs in the form of therapy, which he is required to attend to avoid a prison sentence (for the aforementioned bloody fight he started). The reason he is deserving of this special treatment is because, well, he’s a genius, and that exceptionalism is made all but explicit in both the movie’s dialogue and its underlying moral architecture.

He doesn’t want to do therapy and does his best to bewilder or insult every therapist he gets matched up with, until Robin Williams comes along, eventually tricking and forcing Damon into a breakthrough moment: acknowledging he deserves love and that being abused wasn’t his fault.

Breakthroughs can certainly happen in therapy. It’s also really important to affirm that we are lovable. If we were abused, we need to be able to recognize that it wasn’t our fault. Pretty much everything else about this, though, is so, so wrong.

You can’t be forced or tricked into psychological and emotional growth. People aren’t psychological puzzles that someone with a fancy degree can just unlock. When I was ten years old I had my psychologist dangling on a string. When I was locked up in a psych ward at 17 after a suicide, it took me five minutes to figure out what the head warden (psychiatrist) wanted to hear me say before he would sign my release. Not because I was smart, but because no one has the leverage on our own minds that we do. If I had tried solving or healing them, I would have been just as unsuccessful as they were with me.

Healing has to be a self-guided process that we define and that we commit to. A therapist can help or impede that, but they’re a secondary part of the equation. If we do commit, there’s still the question of what we’re committed to, what kind of healing, what extent of self-reflection? If we’re only thinking about our own pain and not the pain we might be causing others, a good, conscientious therapist might help us discover this thing called empathy by asking the right questions, but that goes nowhere unless we decide to follow that path.

I want to go back to the moment of the breakthrough. Crying, letting out a lot of sadness, acknowledging we’re walking around with an open wound – all of these are good things. But that’s only the beginning of healing, whereas this movie portrays it as pretty much the final step. And I think this is noteworthy, not because this movie singlehandedly defined masculinity for a whole generation, but because I don’t know many people with a compelling vision of what real healing actually looks like.

After his breakthrough, Matt Damon’s character flips a switch. His problem is resolved. He can go back to being a more levelheaded version of his stoic self, but now making the right choice – which is to turn his back on a soulless but high-paying career he has access to since he’s, you know, a genius, and instead leave behind his friends, his community, his past in order to choose romantic coupledom… with the person he was abusive towards… (which is maybe problematic, not because I have any dogmatic rejection of love, but because I think at the very least we should be wary of a “being in a couple vs. having friends and a community” framework, and because people with unhealed trauma tend to have an easy time trying to save themselves and avoid their problems by burying themselves in codependent relationships).

Thinking back on my own experience, I had a couple of vital breakthroughs with EMDR, which is especially suited to helping us reconnect feelings to experiences and memory to wounds. This is really helpful if our coping mechanisms involve dissociation or compartmentalization. But in my experience it didn’t help me undo those coping mechanisms or find healthier ones: I’ve had to turn to other resources and other techniques to get better at that. Awareness of the problem wasn’t enough, I had to decide all over again to keep going. It was never a straight path, and it was never downhill. Everywhere I found myself, I had to respond to the situation at hand, figure out my needs as they changed, and commit to a new path forward.

Those breakthroughs I had were only the third step in what will be, hopefully, a lifetime of doing what I need to be doing, after so many years of stagnation and misery.

The first step was acknowledging I had a wound that I had been unable to heal and that was continuing to hurt me and others. The second step was finding the resources that would enable me to begin an effective healing process.

Understanding the extent of the wound helped me immensely, but it was a rude shock when I discovered that knowledge without action doesn’t actually change our behaviors. Knowledge can also be disembodied, it can also be compartmentalized. Especially if we’ve been compartmentalizing our whole lives.

And that’s where this movie stops short. Trauma can become a part of our self-image, we can imagine we carry it romantically, like a wound that makes us interesting, that makes us worthy of love and support, but that cosmetic change is still a renunciation of agency, of empathy, and of fuller awareness of ourselves as part of much larger collective beings. It’s a renunciation of what healing and transformation actually look like: a million people starting in a million different places, choosing the tiniest of actions and then choosing to follow up, at every waypoint in the journey identifying what we need to do next; connecting with others who are also in it, supporting and learning from one another; trying and accomplishing things that previously we weren’t capable of when we were alienated, underresourced, hurting; transforming and learning as part of the process, including changing our understanding of the process and where we’re going and why and how.

We are not okay where we’re at, and naming that is necessary, but it’s not enough. There aren’t twelve steps or twenty or any other finite number. There isn’t a recipe that works for everybody, and there is no final destination.

There are transformations, though, when enough of us are walking, learning, sharing. There are moments when we suddenly realize that what we’re doing has shifted from escaping to surviving, from surviving to fighting back, and, I imagine, from fighting back to just living. We have to choose it, though: the scary, painful, liberating task of transformation, over a disembodied admission that, yeah, things are grim.

As with any form of progress, we need to recognize that the progress doesn’t get to the root of the problem, but we also need to be prepared by how violently upset the Right gets when mainstream society makes any concessions to criticism. If this reactionary rage builds up and finds effective strategic vehicles to latch onto, then we get a backlash and an unapologetic return to traditional masculinity, even though the “tradition,” every time, is updated and modernized, every bit as new as the progressive version, but with a different repressive logic guiding the changes.

Remember that trauma does not always fit neatly within any categorical box that people are talking about in a certain time and place: sometimes we’re not aware of pertinent types of oppression, and other times, life is just extremely painful: if a flood sweeps away your home and kills a family member of yours, that’s going to wound you deeply no matter what demographic categories you belong to.

Concomitantly, being on top of the social pyramid means someone is much less likely to have to deal with traumatic and wounding life circumstances, except for the forms of child abuse that are especially characteristic of the wealthy. Being on top and staying on top means developing a pathological comfort with inflicting harm, with benefiting from decisions that are likely to have a body count and normalizing that by blaming the victims or naturalizing it with some scientific or religious alibi about how “that’s just how the world works,” excusing themselves of any responsibility for their own actions while simultaneously justifying the advantages those actions bring them. They’re uniquely smart, such that they deserve the rewards their actions bring them, and simultaneously, they’re not responsible for their actions because suffering and misery are just ann unchangeable fact of life. And remember: in the vast majority of cases, they’re not acting this way because of unresolved trauma, given how few forms of violence can actually touch the wealthy and powerful. I do think the practice of pathologizing people should almost always be critiqued and avoided, but in this case, this kind of chosen sociopathy is crucial to the way our society functions. And if the lens I’m using is not the best one, we still need some exceptional framework for analyzing the way the elite show up in the world (maybe there’s a “sea change” or tipping point when the self-justification mechanisms we all use become, exponentially, the greatest part of a person’s internal narrative, and these justifications are applied to exponentially far greater forms of harm than the rest of us are ever capable of causing). Without that, too often, when trying to make sense of it all or to figure a way out of this mess, folks assume the ultra-powerful can be reasoned with or otherwise dealt with as people, all evidence to the contrary.

Hey Peter, thank you, that was a well written meditation on trauma. This is a journey I have been on for a long time, since I was a kid, and I totally relate to what you are saying. My healing also started when I realised the harm I was doing to those around me, and I realised that I had to take responsibility for my healing and be fully accountable for my actions. In my case I was told I had a disorder, cptsd (or c-tept), which is a notion I reject, as I understand capitalism as the 'disorder' not my reaction to it. I also find it interesting how many people who identify as anarchists have had these kinds of experiences and wonder if there is a correlation between traumatic experiences of hierarchy and oppression and engagement in anti-oppressive, liberatory politics. For me and some others that I know this is absolutely the case. A small group of us in UK are working around these issues, around collective care and healing in the context of anti-hierarchical thinking, this is good. We are also working on anti-patriarchal structures and opposing the masculine- trauma narratives of the right. I wish you well my friend. markos

Thank you so much for writing this and for the vulnerability. As a fellow therapy-resistent person, in my case because i perfected masking my neurodivergence, i especially appreciated reading your thoughts on therapy. One aspect you don't mention explictly is the power imbalance intrinsic to most therapy settings. Because of that aspect some of us anarchists in San Francisco looked into Co-Counseling in the late 80s/early 90s. Later i dropped it, when i found out it had its origins from disgruntled Scientologists. But the basic idea still sounds very appealing to me, a sort of mutual aid therapy setting. Have you got any experience in something like that? I recently discovered a similar theory called MAST Mutual Aid/Self Therapy. If i understand it right it was developed and practiced by anarchists in NYC. But i have not found others who want to do it yet.